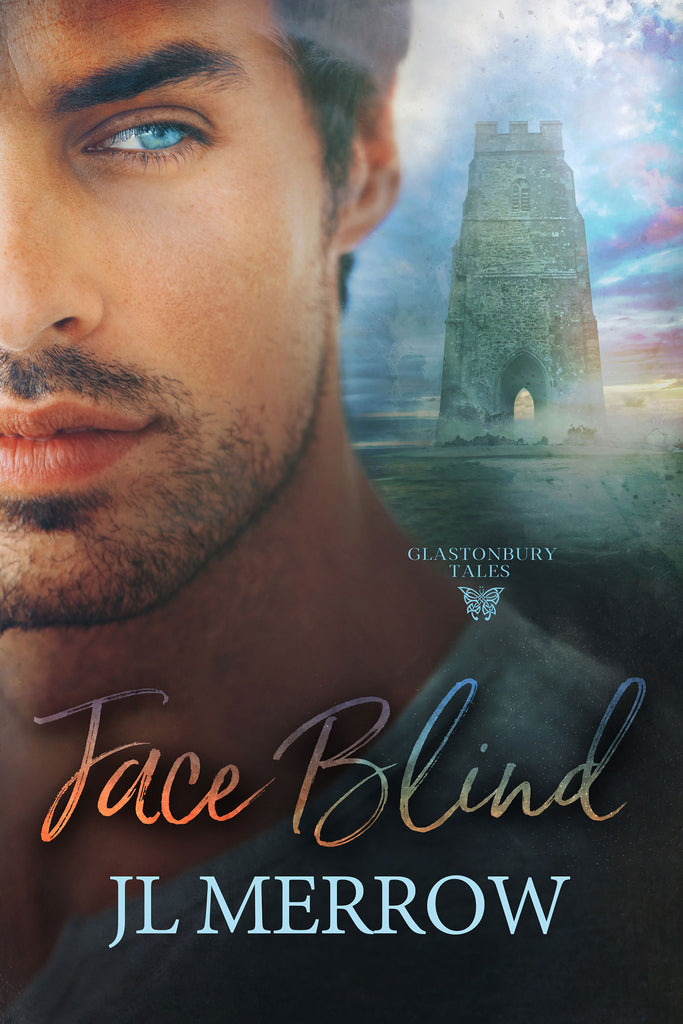

Face Blind

When even friends look like strangers, how will he ever find love?

Corin Ferriman was left face blind by the car crash that killed his ex. Even people he’s known for years are unrecognisable to him. Running from his guilt and new-found social anxiety, he’s moved to Glastonbury, where he knows no one—or does he? Repeated sightings of a mysterious figure leave him terrified that his ghosts have followed him.

Tattoo artist Adam Merchant left Glastonbury at sixteen, escaping from his emotionally distant mother to the father who’d left them seven years previously. Now, at twenty-five, he’s come home to bring his family back together. But in a cruel twist of fate, his mother dies before he can talk to her, leaving him haunted—perhaps literally—by her memory and his unanswered questions.

When Corin and Adam meet again after an eerie first encounter, Adam lays siege to the walls Corin’s built around himself, which start to crumble. But there are ghosts haunting them both, and while Adam longs for a connection beyond the veil, Corin’s guilt leaves him in angry denial that there could be anything after death. With the liminal festival of Samhain fast approaching, neither man is sure what’s real and what’s just a trick of the mind—or maybe something worse.

This title comes with no special warnings.

Caution: The following details may be considered spoilerish. Click on a label to reveal its content.

Heat Wave: 4 - On-screen and mildly explicit love scenes

Erotic Frequency: 2 - Not many

Orientation: bisexual / pansexual, gay

Tone: gothic, humorous, realistic

Themes: abandonment, abduction/kidnapping/hostage (actual), acceptance, cheating (past lover), child abuse / neglect, disability / disfigurement, family, found family, geeks / nerds, ghosts, grief, heritage, isolation, legends, protection, reunion, self-confidence, self-discovery / self-reflection, stalking / harassment, the power of stories, traumatic brain injury

Settings: coffee shop, pub, small town, store, suburbs, tattoo studio, United Kingdom

Chapter One

It was later than Adam had thought, and gathering clouds chased the setting sun. Maybe he wouldn’t go up to the top of the tor to visit the tower, the sole remnant of the church built by his namesake. Abbot Adam of Sodbury, and hadn’t the other lads had fun with that name when they’d all been in school?

It wasn’t really a place for laughs, though. A later abbot had died there, hung, drawn, and quartered for his faith, along with two of his monks. A death like that had to leave echoes through time. It was easy to imagine their ghosts haunting those blood-soaked stones.

Unusually, there was no one else around. Then again, Adam had taken the less well-trodden, steeper path from the east rather than follow the tourist trail up from Chalice Well. And it was a chill day turning into a cold evening, the lowering clouds threatening a return of the day’s rain. Maybe he should have put on something better suited to the weather than his worn leather jacket. He’d never had the knack of thinking ahead like that.

What would it be like to have the sort of mother who always insisted on you wearing a waterproof and taking an umbrella? Who wrapped a hand-knitted scarf around your neck before they let you out of the house? Adam huffed a bitter laugh as the first raindrops hit his face. He could remember those same lads from school complaining about being smothered, when at fifteen, sixteen they were clearly grown men who didn’t need their mums anymore.

Even then, he’d felt a shameful twist of longing for that sort of care. His mum, when he’d told her he was going out, mostly used to give him a blank stare or a nod. But every now and then, he’d get a “Don’t be late back” that had actually sounded like she meant it, like she cared about him—until a switch would flip, and she’d go back to her usual, distant self.

The rain was coming down in earnest now. Perversely determined to make it to the top after all, Adam hunched his shoulders and lengthened his stride. Raindrops stung his cheeks as the wind tugged at his jacket. Should he have done more to mend their relationship? Tried harder? Tried sooner?

The ache in his legs from the steepening climb was a welcome distraction from the turmoil in his heart. It wasn’t like she’d ever given him any encouragement, was it? The last time he’d come up from London to see her stood out vividly in his memory, like a single painting in a gallery targeted by vandals. She hadn’t smiled when she’d opened the door to him. Hadn’t shown any interest in his life.

When he’d moved back here a month or so ago after nearly a decade away, he’d wondered if it would be different. Would absence have made her heart grow fonder? Or would all maternal affection have withered away, dead from lack of nurture?

He’d never know now. Maybe it was better that way. He could tell himself the terms of her will meant she had loved him; she just hadn’t been able to show it. Tell himself it wasn’t guilt that had made her leave everything to him.

Head down against the driving rain, Adam almost walked straight into the tower, stopping himself in the nick of time. The stone was slick when he touched it with wet fingers, proving it was really there. That he was. Still trailing his fingers on the stone, he rounded the corner of the tower to the more sheltered side that looked down towards the town. The old structure felt warm at his back as he gazed over pocket-sized fields and a toytown Glastonbury, made hazy by the weather. As he stood there, a thick mist blew over the ground below him, and within seconds it was as if he were cut off, standing on an island in a cloud.

A man could almost believe in the legends that surrounded the tor, at a time like this. Could imagine, as he had as a child, the wild hunt setting out from under the hill, the fairy horde led by Gwyn ap Nudd, the horned god of the underworld.

Adam smiled to himself and shook his head. Time to head back. His hair was soaked, water dripping into his face and down his neck. He’d need a hot shower and a good meal when he got back home—if those gits he lived with hadn’t used all the hot water and occupied all the rings on the stove already.

The rain had slackened to a heavy drizzle as Adam started down the path, moving quickly so as to warm himself up. Mist shifted and swirled in front of him, now thicker, so that he could barely see a few paces ahead; now thinner, allowing a view almost to the bottom of the hill. It was strangely quiet, as though sound were deadened, but then, there was no one else here to make a sound.

Or was there? Casting his gaze around, Adam caught sight of a dark figure some way distant, near the other path—the two were more or less at right angles this high up—and was blindsided by a sudden shock of familiarity.

“Mum?” he whispered—but it couldn’t be, could it?

Christ, that was her coat, the long dark one he’d seen only hours ago in the downstairs cupboard. And her hair, worn loose and flowing over her shoulders, like when he’d been little.

For a moment, he could swear she was singing: a song he’d forgotten, until now, brought from the Scottish Highlands of her birth: I left my baby lying there . . .

Then the mist rolled over the hillside and she vanished from his sight.

His pulse throbbing in his ears, Adam ran across the grass. But when he reached the spot where he’d seen her, there was no one there. He scrambled farther, feet slipping in the wet grass. How could she have disappeared? He stopped, panting, and gazed all around, willing the mist to clear.

There. A figure on the Chalice Well path.

Not Mum, though. Disappointment dropped like a lead weight in Adam’s stomach. It was a man, walking alone, head down, probably keen to leave the tor before darkness set in. Adam slip-slid down and around the hill to him. “Did you see her?” His voice came out rough. Harsh.

No wonder the man took a step back, eyes wide. “What?”

“There was a woman. Older. Uh, about sixty. Just now. Did you see her?”

The man stared at Adam. He was attractive, Adam noted distantly, with broad shoulders and gelled-up hair. For all his modern looks, there was something strange about him, as though he’d sprung from the legends that surrounded the tor. With the height of him, and that solid build, maybe even something dangerous.

“I haven’t seen anyone here. Apart from you,” the man said at last, his gaze still oddly intent. “Did you . . . lose her?”

Christ. Adam shook his head. He was going mad. His mum was dead, and her coat was in a bag waiting to go for recycling. “No. Sorry. Mind playing tricks.”

The stranger flinched—or was it simply a jerky hunch of the shoulders?—and took a step back. Adam was put in mind of a stray cat, unsure if the outstretched hand would mean a pet or a blow. He didn’t say anything. Well, who would want to talk to someone who’d admitted to seeing things?

“Sorry to bother you.” Adam turned away to make the weary slog back around the hill and down to where he’d parked the Yamaha.

He kept his eyes open on the way. But his mum, if she’d ever really been there, had gone.

Chapter Two

Rain had been falling steadily that afternoon, and Corin had been relieved to have reached Glastonbury in one piece. The drive down from Wiltshire had taken the best part of two hours, instead of the one-and-a-half Google estimated. Although he hadn’t needed to use any motorways, there had still been some idiots driving way too fast, and he’d stopped a couple of times to let them go by.

Having pulled into what he hoped was the correct parking space, he hauled a few bags out of the Volvo and up the external staircase to the two-bedroom attic flat that was his new home. The woman who opened the door to his knock introduced herself as the landlady. She handed him the key, gave him a quick rundown of the quirks of the boiler, and left, unfurling her umbrella, with a parting, “We’re just down the road if you need anything, my lover.”

“Thanks.” Corin remembered to smile, and shut the door behind her. Then he slumped down on the sofa. It sagged in the middle, as if used to someone heavier. Corin wondered who’d had the flat before him. Why had they left? Moving on to something better?

Or running away from something worse, like him?

He stood up again and gave himself a mental shake. He’d chosen to leave Avebury, and he still believed it was the right decision. The flat might be smaller than the one he’d left, but it was light and airy, and he’d been sold on the place as soon as he’d seen the view from the windows. Up high in the attic, he could see over his neighbours’ rooftops to the tor beyond. Or, if he preferred, he could gaze down into the street to watch life going on below. Corin had originally thought of getting a place out in the countryside, but here, he could have the feeling of being away from it all while still being handy for the shops. The fact that the flat had a reserved space in the residents’ car park was the icing on the cake.

If he was being spectacularly honest with himself, he could admit that hiding in some lonely hermitage wouldn’t have been the best idea for his mental health, so it was probably just as well that the only country homes on the market had been ridiculously large houses with equally ridiculous price tags.

And running up and down the stairs to the front door will keep me fit, he thought ruefully as he braved the rain several more times to fetch the rest of his boxes and bags. Amazing how much stuff one single man could accumulate. The larger bedroom, the one he’d be sleeping in, had a fine view of the roof and tower of St. John’s Church. Corin hung up the few items of clothing that warranted the attention in the cheap fitted wardrobe and shoved the rest into the chest of drawers, an antique pine monstrosity that dominated the room and failed to match with anything else. Then he took towels into the bathroom, making a mental note to buy some soap.

As he hung a hand towel by the sink, his gaze fell on the mirror fixed to the wall with capless screws that were rusting contentedly in the twilight of their lives. He froze, still not used to a stranger’s face staring back at him. The stranger had mid-brown hair, cropped aggressively at the sides to blend in with his three days’ beard. The top was gelled up, except for where the rain had flattened it. Corin ran his hands through it, forcing it to stand up for itself again. Did the stranger look better after that? Corin’s judgement was an unreliable beast, these days, but he’d made an effort. “See, Declan? I still care,” he said aloud.

His brother didn’t answer, because he was back in Swindon, probably trying to explain to all their friends why Corin had left so suddenly. And why he was so bloody stand-offish these days.

It had been hard in hospital after the accident. Harder yet when they’d sent him home with a bundle of information about prosopagnosia—face blindness—and a list of coping strategies to practice. At least when somebody had come up to his bed in the ward with a determined smile and maybe a small gift, he’d been able to be fairly sure they were someone he knew, even if he hadn’t been able to tell who they were—often until they’d been talking for several minutes. There had been one visitor he’d never managed to identify, putting the young man off after an awkward conversation with claims of tiredness that hadn’t, in fact, been faked. It was exhausting straining for every clue to who a person, apparently of some importance in his life, might be.

Coming out with a flat Who are you? didn’t help. He’d only done it the once, and the woman had flinched as if he’d slapped her. Then she’d pasted on a smile, identified herself as a neighbour in a slow, high-pitched voice as though he were a child or an elderly dementia sufferer, and left.

Returning to Avebury, his home village, had been a nightmare. It was a small place, where he knew dozens of people well enough to say hello to. He’d never realised how little there was to distinguish them from one another. Everyone wore dark, casual, practical clothes, suitable for walks in the countryside or playing with the kids. Corin had seemed to have an unfailing knack for guessing wrongly which ones he should greet, and those who’d eye him strangely for it. Even when he got it right, it still felt wrong—as if by losing their faces, he’d lost all connection to the people he knew.

When he’d found himself eating baked beans without toast for lunch to avoid having to go out, Corin had decided enough was enough and started searching for a flat in a town where every visit to the local shops wouldn’t be a social minefield.

So here he was. And, hopefully, things would be better here, where he could look forward to going out, rather than dread it. He’d been planning to celebrate his new home with a takeaway for dinner, so Corin threw on a jacket, shoved on his trainers, and set off, with a stop at the car to grab his umbrella.

There were two takeaways on his street—a small, family-run Chinese place, and a larger Indian that was also a restaurant. Chinese tonight. The place had an inviting air, with a short, white-haired lady behind the counter and a bright-red lucky cat waving in the window. He would give the chow mein a try, after he’d had a bit of an explore. Or maybe the crispy beef. Hell, why not both? He was celebrating, after all.

Corin took a meandering walk through the centre of town with his umbrella and let the rightness of coming here seep into his bones. Glastonbury’s many old buildings spoke of its rich history—the George and Pilgrims’ Hotel, and the abbey itself, to name but two. Maybe after he’d lived here for a while he’d get tired of the wacky witchiness of the shops that surrounded them, but he doubted it. He didn’t have to buy into the new-age spirituality of the town to appreciate its uniqueness—so unlike the majority of cookie-cutter towns across the UK, all with the same chain stores and restaurants. In a place like this, he wouldn’t be able to forget where he was.

And then there was the tor, rising to the east. That conical hill topped with its square, blocky tower had been the first thing he’d seen, driving into Glastonbury. Its height made it visible for miles around. The rain had finally stopped, and Corin had a sudden urge to go there. To plant a flag on the local landmark, as it were. Not having internalised how big Glastonbury was, Corin debated whether it would be sensible to go back to his flat and fetch the car. In the likely event his damaged brain couldn’t find the way back home unaided, it’d be easier to use the car’s GPS than the one on his phone. Especially if the rain set in once more.

Against that was the fact he’d driven two hours to get here, and he really didn’t want to get back in the car again today. Okay, so he’d been fine on the A roads coming over, and traffic in town wouldn’t be moving very quickly . . . No. Just thinking about taking the car was sucking all the joy out of the idea. Corin took another glance at the tor to get his bearings, and set off on foot.

For once, his luck was in. Aided by the brown signs around town, he found the start of the tor footpath without too much difficulty, a short distance past the Chalice Well as his tourist map had promised.

The footpath was wide and well-maintained, swept clear of fallen leaves from the trees that bounded it. Another brown sign promised he’d get there in fifteen minutes—good news, seeing as the sun was now close to the horizon. The way was steep, and Corin could feel it in the backs of his legs and his buttocks, which apparently reckoned they’d had quite enough of a workout moving his things into the flat. A set of long, shallow steps led up to a kissing gate, and once through it, he was out in the open, the green hummock of the tor rising before him.

A dark figure on the other side of the gate was bundling up a sleeping bag. Corin had his hand in his pocket before he heard the predictable “Spare some change?” in a weary, toneless voice. He didn’t envy anyone living on the streets as the days grew colder.

“Here you go, mate.” Corin dropped a couple of quid into their hand. In the twilight, it was hard to make out any details of the black-clad figure with their hood pulled down low over their face.

The rough sleeper didn’t speak again but gave Corin a sketchy salute in thanks before returning to packing up their few goods.

The path led on up through a field of sheep to another gate, which seemed to mark the base of the tor proper. A few trees grew there, one of them adorned with colourful ribbons. Prayers? To which deity? The gradient became steeper, and there were steps to aid the weary climber. Corin halted for a moment to turn and view the way he’d come. Glastonbury town lay before him, and beyond it, the sun sunk low in the sky.

But now rain was setting in. Putting up the hood of his waterproof, Corin headed onwards, following the path on its winding route towards the summit of the tor.

As he neared the top, the rain slackened again. The wind, by contrast, picked up sharply. It ruffled Corin’s hair as he stopped once more to put back his hood and turn in a slow circle to gaze over the Somerset Levels—all cosy English countryside these days, with villages and patchwork farmers’ fields, but thousands of years ago he’d have been surrounded by marshes. Glastonbury Tor would have risen out of them, high and dry, a true island. No wonder they called it the Isle of Avalon to this day.

St. Michael’s Tower, at first half-hidden by the brow of the hill, grew taller as he approached. Its sandstone stood out darkly against the grey skies visible around and through it, the arched doorway at the front going straight through to the back. Corin shivered. Those strong winds had ushered in a rolling mist and the light was fading fast.

Better get a move on if he was to make it to the tower and back before dark. Corin increased his pace, half jogging up the low steps of the pathway. By the time he reached the tower, he was warm with the exercise and relished the wind on his face. There was no one else around, which had to be a rare occurrence for a place so iconic. He wanted to make the most of it.

A moment later, a sinking sensation came with the realisation that he wasn’t, in fact, alone: a lean figure was visible on a second path heading down from the tower. Corin must have just missed meeting him at the top. Further unease greeted the view—or rather lack of it—of his own path. Damn it. He’d have to cut short his walk here if he didn’t want to risk getting lost in the dark and the fog. Still, he had all the time in the world to make a return visit. Telling himself to be philosophical, Corin started to make his way back towards civilisation.

He hadn’t gone all that far when he was startled by a shout from only a few feet away. Corin whirled. How had he not heard anyone approaching? “What?” he managed, heart racing.

The man standing there was dark-haired, wet, and bedraggled, dressed in a black leather jacket that didn’t appear to appreciate the soaking it had got. “There was a woman. Older. Uh, around sixty. Just now. Did you see her?”

The earnest, almost desperate way he spoke was arresting. His accent was unexpected—more London than Somerset. Corin gazed at him in a futile attempt to find something visually unique about the man. Something memorable. But his features were entirely regular and his build well-proportioned. Useless, in other words. “I haven’t seen anyone here. Apart from you. Did you . . . lose her?”

The man seemed to hunch in on himself, and Corin wished he could offer comfort. “No. Sorry. Mind playing tricks.”

It hit him like a blow. God, you too?

“Sorry to bother you,” the man said before Corin could bring himself to voice the admission, and ran back in the direction he’d come from.

An inexplicable sense of loss assaulted Corin. Why should he care that a man he’d never met before—and wouldn’t know if he saw him again—had gone? What was it to him if the stranger did or didn’t find the woman he was looking for? If she even existed, that was. Rattled, the relaxation from walking on the tor totally gone, Corin increased his own speed back towards the town. Back towards the sanctuary of his car and his flat.

As he reached the gate, his unease intensified. Damn it, had the strange man been seeking the homeless person? Corin had forgotten all about them in the stress of the moment, and they’d now disappeared, hopefully to somewhere sheltered. Not that Corin would have been able to give any useful information about them. And while he was the last person to trust his judgement on these things, they hadn’t seemed anything like as old as sixty. Nevertheless, the nagging sensation that he should have done more followed him all the way down the path.

Walking back through town five minutes later, pathetically reliant on his phone’s GPS, he wished he’d brought the car, after all. Everything looked different in the twilight, and the gung-ho spirit that had prompted the excursion had vanished with the sun.

And you don’t run into unexpected, demanding people in the car, either.

At least, not unless you’re driving without due care and attention.

Chapter Three

Before he went walking with ghosts on the tor, Adam had spent the day at his mum’s house. They’d buried her the previous Thursday, on a bright sunny afternoon that had made the few flowers shine bright with jewel tones. It had sparked a rare memory of the living room curtains when he’d been little, and how she’d used them to teach him the colours of the rainbow.

As he’d parked the Yamaha outside Mum’s house way too early on that damp Sunday morning, Adam had thought of those curtains again. When had they come down? The ones hanging there now were in the muted, drab tones he recalled from his teens.

His sister Evie’s VW was already there, and as he pulled off his helmet, she got out of the car and came to join him. “Managed to get up on time, then?” she greeted him.

Adam made an effort not to take offence. “Wasn’t easy. The lads were up drinking till late last night. And no, I didn’t join them, but they weren’t exactly quiet. Why didn’t you go on in?”

Evie gave a tiny shrug. “Thought I should wait for you, that’s all.”

She turned away from him, so he couldn’t tell if that was a dig or not. Maybe wouldn’t have been able to tell even if he’d seen her face. With a nine-year age gap, they’d never been close, and all his time away hadn’t helped.

He was only beginning to get to know her again.

Mum’s house was one of the smaller, older houses on the Roman Way. It and its semi-detached neighbour were reached up a flight of thirteen stone steps from the street, and the elevation meant the tor was visible from the front garden. Adam stopped for a moment to appreciate the familiar view, then turned a critical eye on the garden itself. The front lawn needed mowing, but the shrubs at the side appeared healthy.

“She looked after the place okay.” Was Evie’s tone defensive? Or accusing because Adam hadn’t been there to help Mum out?

Or was he projecting his own feelings onto her? “I’m sure she did. It’s not like she was old, old.”

Evie drew in a breath as though she was about to speak, but didn’t, so Adam strode up to the front door. His newly cut key stuck in the lock, and he jiggled it, suppressing a curse.

“Shall I do it?” Evie asked, her breath warm on the back of his neck from where she’d huddled into the tiny porch with him to escape the drizzle. Apparently she still saw him as the little kid who needed help with everything.

“No, I think I’ve got—” The key turned all of a sudden, and Adam bashed his knuckles on the door jamb. Biting his tongue once again, he pushed open the door to his childhood home. The narrow hallway was much as he remembered it from the last time he’d visited—shit, was it over three years ago now? His conscience, which had already been prodding him, stabbed him in the chest.

But it wasn’t like Mum had wanted him there, anyway, had it? She’d dithered and fidgeted, making him a milky cup of tea as if she’d somehow forgotten he’d hated the stuff all his life. He’d choked it down anyway. It had given him something to do.

Evie had been there that time too. Had Mum asked her to come as a buffer between him and her? Mum had talked to her about local things and people they both knew—and spoken to Adam as though he were a stranger. Give Evie her due, she’d done her best to include him, but Mum hadn’t budged. In the end, she’d stood up, said, “I must get on,” and made it clear Adam could kindly sod off.

He’d been meaning to visit again, since he’d moved back home to Glastonbury in August. Had asked Evie to mention it to Mum, get her prepared for it. He’d thought he’d had plenty of time.

Mum’s heart hadn’t agreed.

“I cleared out her fridge last weekend and donated all the cans and things to the food bank,” Evie said, snapping Adam back to the here-and-now.

“So you were fine coming here without me last week?”

She reddened and folded her arms. “That was before we read Mum’s will.”

“That wasn’t what I . . . Look, I don’t care what the will says. This house is as much yours as mine. More, even.”

Evie didn’t look at him. “Anyway, I thought we’d start with her clothes. They’ll need sorting and bundling for the charity shop, if they’re good enough, and textile recycling for the rest.”

“Right.” Adam could do businesslike too. “What about furniture? Is there anything you want there? Or is that all for the charity shop too? We can get them to collect, and they can take the clothes as well.”

“We’ve got a house full already.” Yeah, and her and Paul’s taste in furnishings was worlds away from Mum’s mishmash of stuff bought second- or third-hand. “But what about you?” Evie went on. “Won’t you want to keep it?”

“Me? I’ve got one room in a shared flat. The smallest room. Where would I put any of Mum’s stuff?”

Evie pushed her glasses back on her nose. Large and squarish, they shouldn’t have suited her but somehow did. “You don’t have to sell the house. The mortgage is paid off—if nothing else, Dad was good for that. You could live here. It’s just as convenient for where you work as that flat of yours.”

Adam fought down the anger on Dad’s behalf. She had good enough reason to resent him, whether she knew the truth or not. “Yeah, but if I sell the place, I can give you half.” He’d had it all sorted in his head—he’d use his half of the money to get a flat somewhere he didn’t have to share a kitchen and bathroom. He hadn’t imagined getting a whole house to himself.

“That’s not what Mum wanted. And I don’t need the money. Paul and I are doing quite well between us.”

“Yeah, but it’s not fair.”

“It’s fine.” She coloured. “And maybe I’d like the house to stay in the family, have you ever thought of that?”

“Is it really that important to you?”

She turned away. “It doesn’t matter. It’s your choice.”

Should he give her a hug? Adam hesitated but gave in to the impulse anyway. Evie took a sharp, startled breath, but then relaxed into his embrace.

“I’ll think about it,” he told her. “I wasn’t expecting it, you know? And I haven’t got a lot of great memories from living here.”

Evie sniffed, then broke free from his arms. “You were always her favourite, when you were little, do you remember that?”

Adam shook his head. “Nope. Don’t all siblings think the other one’s the favourite? What I remember is the way Mum’s gaze used to slide off me, like she wasn’t sure I was really there. Or ought to be, whatever.” He’d been a constant reminder of her guilty conscience, hadn’t he?

“She wasn’t always like that. Something changed,” Evie said slowly. “I’m not sure what, or when. But it doesn’t matter now,” she added briskly, right when he’d made up his mind to tell her.

Did it matter now? Maybe it didn’t. They were both grown adults, not kids—okay, one kid and one uni student—trying to work out why Dad had left them. Why things had been so bad in the months—years, maybe?—before he’d gone. That time was all jumbled up in Adam’s head, memories telling him things had happened before they really had. Pictures in his mind that had never been real. Echoes in his mind of childhood nightmares, most likely.

Evie was already heading upstairs, so Adam hastened to follow her. “Do you know where Mum kept her jewellery?” he asked. “We should sort that out first, in case there’s anything valuable. Don’t want to leave it lying around in an empty house.”

“I, um, did that last week too. I’ve got it at home.” She hesitated, tucking a strand of blond hair behind one ear. “I know legally speaking it’s yours, but there’s a couple of rings I’d—”

“Bloody hell, Eves. Of course you should have them. I mean, all of it. What am I going to do with Mum’s jewellery? Give it to the girl I’m never going to marry?”

“Just because you’re gay doesn’t mean you won’t have a daughter one day.”

“Could say the same for you. Uh, apart from the gay thing.”

Evie shook her head firmly. “No. Not going to happen.”

“You might—”

“Don’t say it. I mean it. I’m not going to change my mind, and Paul’s fine with that.”

“Right, then if you’re that worried about cheating my hypothetical kids out of their inheritance, leave it to ’em in your will. Seriously, it’s yours.”

“Okay.” She looked down. “I wasn’t sure you were going to be so, well . . .”

“Reasonable?”

“Nice, I was going to say.”

<ISBN: 978-1-62649-968-3

Release Date: 10/10/2022

Price: $4.99