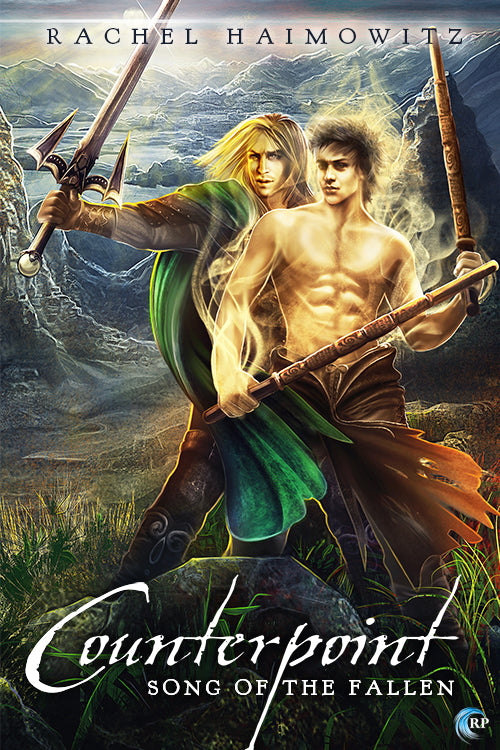

Counterpoint (Song of the Fallen, #1)

It is the twilight of mankind. Depleted by generations of war with a race of dark beasts, humanity stands on the brink of extinction. The outlands are soaked with the blood of the fallen. The midlands are rotting with decadence and despair.

Elfkind, estranged by past crimes, watches and waits for nature to run its course.

And then the two collide.

Ayden’s life has long been guided by two emotions: love for his sister, and hatred of all things human. When he’s captured in battle, he is enslaved in the service of a human prince, Freyrik Farr. Freyrik’s always known elves to be beautiful and dangerous, but never has one affected him as deeply as Ayden. Teetering on a dagger’s edge between duty and high treason, Freyrik discovers that some choices can change a life, and some an entire world.

Between prejudice, politics, pride, and survival, Ayden and Freyrik must carve a new path, no matter how daunting. For nothing less than the fate of both their peoples rests on the power of their perseverance—and their love.

Note: This is a second edition originally published elsewhere.

Get this title in the following bundle(s):

Reader discretion advised. This title contains the following sensitive themes:

explicit violenceThis novel features realistic battle scenes and cultural misogyny.

Caution: The following details may be considered spoilerish. Click on a label to reveal its content.

Heat Wave: 5 - Very explicit love scenes

Erotic Frequency: 2 - Not many

Genre: action / adventure, epic fantasy, fantasy, high fantasy, romance

Orientation: bisexual / pansexual, gay

Age: 20s, centuries old / immortal

Tone: exciting, gritty, literary

Themes: abduction/kidnapping/hostage (actual), abuse, alpha/alpha, angst, bisexuality, enemies to lovers, hurt / comfort, interracial/multicultural, interspecies, military, power imbalance, protection, slave / capture (actual)

Chapter 1

Ayden awoke to wrongness.

He shoved his furs aside and tuned his inner ear to the forest’s song—the bass hum of the trees, the trills of insects—a thousand points of sound merged in near-perfect harmony. He sniffed the air as he listened, detecting nothing but a faint whiff of last night’s cook-fire, the loam of the forest floor, the comforting scents of the massive red cedars and the stream running by his campsite.

And there was the wrongness, the faintest whisper of jagged notes worming through the forest song. Had a human dared to cross into their lands?

Ayden’s lips pulled back from his teeth in a grin entirely void of humor.

Time for a hunt.

He unwove the branches of his shelter with an impatient mental hum and stepped out into the first light of day. A second sound reached his ears then, a physical one this time: dull hoof beats and snapping branches, faint but rising by the moment. The approaching racket might be nothing more than an animal on the hunt, but he dare not take that chance.

He stooped to grab his kit, lashing his furs to his satchel and slinging it and his fighting sticks across his back. Then he dropped a sleeping dart into his blowpipe and once again cast both inner and outer ears to the ruckus rushing closer, closer . . .

And sighed, relieved, when he recognized the sound for what it was: a pair of wild boars tearing down the path to his campsite. He lowered his weapon and tuned his other hearing to the boarsongs, churning crescendos of urgency and blind rage. They were almost upon him already. Ayden spun a soothing melody in his mind, a half-forgotten lullaby, and sent it to weave through the boars’ frantic tempos—

The two boars emerged into the clearing, drawing to a halt not two feet before him, heads bent and hooves pawing at the earth.

“What haste, fierce ones?”

Of course they couldn’t understand him, but it felt good to use his voice again.

Not surprisingly, the boars responded about as intelligently as most people would: one snorted, and the other one squealed.

The squealer took a hesitant step forward and to the side, then stopped again. Its gaze shifted from Ayden to the path beyond and back. Ayden closed his eyes, tried to hear what the boars were hearing, what was driving them forward so urgently. And there it was again, the wrongness, just a whisper yet but a precursor, he knew, of a powerful wail to come: the Hunter’s Call, summoning beasts to twist with hate before siccing them upon the human realms.

“Ah.” Ayden opened his eyes and nodded at the boars. “I’d not discourage you from such a noble task, but you must know the humans will kill you?”

The squealer took another step forward. This time, the snorter joined him.

Who was he to argue with that?

He stepped aside. Freed of his influence, the boars bolted across the clearing and disappeared back into the dense wood.

Ayden took off after them at a hard run. He followed them for hours, even though he knew with fair certainty where they would go. Indeed, they did not disappoint.

The sun had crested the sky by the time they reached the boundary between the elven and Feral lands, where a foot-wide crack cut through the forest like a fatal wound. No life grew near the fissure for twenty paces, the very earth scorched into volcanic rock and great sheets of muddy glass. No elf had crossed the fissure for nearly three centuries. The boars, however, trotted over without pause, drawn inexorably by the Call that wailed like death in Ayden’s inner ear.

Ayden stopped short, loath to set foot or toe upon the deadened earth.

Instead he found the tallest tree at forest’s edge: a massive red cedar, its trunk as big around as twenty of him and its lowest branches a good dozen paces overhead.

“I don’t suppose you’d offer me a hand up?” he asked, placing a hand upon the trunk and trying to coax a branch to bend within his reaching.

Alas, this tree had sung its melody unchanging for over two thousand years, and it had no interest in shifting for a whelp such as he—never mind that he’d seen a century or eight himself.

Ah, well. He hadn’t really thought it would. He fished his steel bearclaws from his satchel, buckled them onto each boot and hand, and started up the trunk the hard way.

Long minutes later, sticky with sap and quivering with fatigue, Ayden broke through the canopy. He dug his farseer from his satchel and peered through the lens. From this new vantage point over a hundred paces high, he could see south across the cultivated human lands for nearly three leagues, and the same distance west across the forest canopy of the Feral lands into the Myrkr Mountains. A few leagues southwest, in the direction the boars had gone, he spotted a dozen crowned eagles gliding over a low mountain peak. No, not just gliding . . . they were circling as a pack, wingtips splayed like fingers on a massive hand.

Crowned eagles never flew in flocks, could barely tolerate each other even when mating. He could hear the wrongness pouring from them in pounding, discordant waves.

Command would wish to know of this. Ayden balanced himself between the trunk and two narrow branches, letting them take his weight, and focused his mind on forming a signal cloud. ’Twas no easy feat for him, a naturally adequate musician at best, to hear the cloudsong so far away and amongst so much noise from the forest below, but at last he detected faint threads of it, high notes jittering chaotic and fast in the upper sky, and he shaped them with his mind into clear lines and measures. Above him, three clouds merged into two and formed the symbol for Ferals and a navigational marker.

He held them as long as he could, gritting his teeth against the strain. But his clouds drifted quickly, and a moment later he gave up, panting, and let them scatter. No matter, though; Command would have seen the signal immediately and understood.

The Surge was building.

***

Having done all he could for now, he turned his thoughts to a meal, and water, and setting up camp for the night.

Climbing down the massive cedar was, to Ayden’s chagrin, nearly as taxing as climbing up it had been, and it didn’t help that the Call was growing more strident by the hour. Halfway down, a small herd of caribou bucks in full rack raced by his tree and crossed the border. As he reached the ground, a squirrel whizzed by, and he could not help but wonder what harm such a harmless creature could possibly inflict. But the Hunter’s Call would not draw it for nothing; surely it had some purpose.

’Twas not his concern, though. His empty belly, on the other hand, was very much so. Fortunately, he knew these woods well, and before an hour had passed he’d gathered a feast of mushrooms, huckleberries, wild onions, miner’s lettuce, and hazelnuts. There was no water source nearby, but ’twas easy enough, even for him, to draw it from the moist air; he untwined the dewsong from the airsong and guided the trickle into his upturned mouth until his thirst was slaked. He drew more to fill his canteen, then climbed back up to the first branch of the cedar he’d scaled before and unrolled his furs. If he slept on the ground this night, he might very well be trampled. Besides, ’twas best to be prepared should something go wrong: should the Surge for once flow into elven lands, or should the humans, in their desperation or foolishness, try to cross the border themselves.

***

Ayden woke early and alone, wondering what was taking the others so cracking long. Had they not seen his signal? Or were they simply too lazy to travel through the night?

Regardless, he would be well prepared when they arrived. He emptied his bladder, foraged a quick breakfast and a large store of extras, and packed his kit before the sun had cleared the horizon.

Back atop his cedar, he coaxed the leaves and branches to weave into a hunting blind large enough to camp in. From this perch, he had a clear view of the nearest human village a league to the south, and several leagues of their land beyond it. To the west, he could see a few leagues across the Feral woods until the ridgeline cut his view. He spent the morning watching them both, enjoying the solitude and the late summer weather, the many-layered forest song drowning out the worst of the wrong.

He was jarred from his peace round noon by the urgent clanging of bells to the south, and he snapped his farseer toward the human village, where both the temple bell and the bell atop the Surge fortress were ringing madly. The human occupiers of that sorry patch of borderland were dropping tools and baskets in the fields where they stood and scrambling toward safety. Half a league to their west, a mismatched couple of Ferals—a caribou buck and a wolf—were racing toward them. He couldn’t hear the humans screaming this far off, but he liked to imagine that they were.

The Ferals were gaining quickly on a man and a woman who’d been working a distant field; the humans with their two weak legs could never hope to outrun the four-legged Ferals, but they were certainly trying. The man’s longer stride carried him ahead of the woman, but he paused, ran back to grab her hand, pulled her forward again. How foolish and sweet: they’d die together.

From the east rode two archers on horseback, but Ayden doubted they would make it on time.

And indeed they did not. The woman faltered up a steep hillock, and the Feral wolf caught up with her. She crumpled beneath its lunge without a fight, and Ayden gave the wolf a silent cheer for meting out swift justice.

The male—the stupid fool—stopped again, looked back. Probably screamed the woman’s name. Ayden couldn’t make out his expression or hear his song from here, but clearly he was torn. By the time he realized there was no helping the woman and began to run again, the Feral buck had gained on him. The man took but ten steps before the buck, as large in its twisted form as a plow horse, gored him through the back and tossed him aside. The man hit the ground with the grace of a soldier and rolled to his knees despite the gaping hole in his chest. Ayden watched him pull something from his belt—a knife, he thought, from the glint of sunlight—but the man died before he could use it.

The Ferals trampled his body as they charged past, but didn’t savage it. Instead they raced toward the two riders, then veered off to tackle a man who stood paralyzed in the fields. Ayden fastened his farseer onto him and cursed. ’Twas only a scarecrow. He could see that even from here; how did they not? The cavalry was closing in on them from behind, and he found himself waving the Ferals along—he would have called out to them if he were closer, foolish as that was—but he had no hope of swaying their course. The Ferals charged, leapt, knocked down the scarecrow and sent its head flying.

Then the mounted archers reached their range, and they felled the wolf with two shots through the head that even Ayden had to admit were impressive from horseback. The Feral buck turned and rushed them with lowered antlers—gods, Ayden hoped it wouldn’t hurt the horses—but the riders re-nocked their bows in time to take it out.

It was over.

Or not: a third creature, so small that Ayden had missed it before, took a flying leap and scurried right up the leg of a rider. It was on his face before the man could reach for his knife, and he fell from his horse, batting wildly at his head. The other soldier dismounted and killed the Feral rodent, but his companion lay unmoving now, either unconscious or dead. Hopefully dead. That made three kills to three for the Ferals—a definite win. After all, wild animals bred much faster than humans.

The excitement died down after that. The one surviving soldier rode back to town, the bells stopped clanging, the humans returned to work, and a group of men built a pyre for the dead. A lone Feral hawk watched them all as carefully as Ayden did, but none of its friends came to join it.

Speaking of friends, Ayden was growing rather impatient with the tarrying of his own. He gathered his strength to form another pair of signal clouds, just in case, then settled in to wait for the next attack.

***

The scouts arrived about an hour later. Ayden couldn’t see them—they must have been muting their lightsong—but he could hear four of them moving through the forest long before any sound reached his bodily ears. He climbed down to greet them, and found them waiting for him by the time he reached the ground.

Except they were still invisible.

Show-offs.

Ayden looked directly at the space where he knew the one in the lead to be, and a grin crept up his face despite his best attempts at annoyance. “I can hear you, you know.”

The forest before him rippled into the shape of a familiar, smiling elf.

“Afi Kengr,” Ayden said, grasping forearms in greeting. “By the fallen gods, what took you so long? And where are the rest of you? Or does the Council not deign to concern itself any longer with such business?”

Afi smiled back. “Always so impatient, you are.” His three companions, still invisible, spread out to form a perimeter. “Do you know how far we had to travel? And we daren’t ride with the Call so strong—’twould be a shame to have our horses go running right out beneath us past the Crack.”

Ayden conceded the point with a chuckle.

“Anyway, the rest aren’t far behind. But you’re right about the Council, they have grown complacent. I have toenails older than some of the boys and girls they’ve sent this time. But tell me: how far have the Ferals progressed?”

Ayden reported what he’d seen so far, then invited Afi up his tree to take a look. For Afi, of course, the tree bent its first branch. Ayden shot him a dirty look, but stepped up beside him all the same.

“Fret not, my friend,” Afi said, slapping Ayden on the back. “Another few hundred years of practice and they’ll bow for you too, I know it. Shall we race to the top?”

Though Afi didn’t wait for an answer before leaping to the next branch, Ayden grinned and cried, “You’re on, old elf!”

He beat Afi to the top by half a dozen paces.

Once in his hunting blind, they sat back, scanning the landscape and waiting for the rangers to arrive. To the west, a wake of vultures had joined the eagles on the updrafts over the Myrkrs.

“Gods, how can you stand the noise?” Afi asked, pressing his hands to his temples as the Call ratcheted up another notch.

Ayden shrugged. “You get used to it.”

“The view is worth the price, though.”

“Indeed. Will you stay?”

The old scout shook his head. “Command has other plans for me.”

Ayden knew better than to ask what they were. Instead they settled into companionable silence, one eye to the Ferals and the other to the woods behind them.

Their waiting ended half an hour later, when the clutch of junior rangers arrived in a hail of stomping boots and rattling foliage and nervous chatter.

“Ah, younglings.” Afi sounded fond.

Ayden pulled a face. “I was never that green.”

Yet Afi’s clamped, twitching lips told a different story. “Come, greet them,” the old scout said, cutting off Ayden’s indignant response. “’Twould do you good. You’ve been out alone for too long, my friend.”

Ayden snorted. “Climb down a hundred paces for the pleasure of their prattle? I thank you, no.”

Afi shrugged. “As you wish.”

“Signal if you need me,” Ayden called to Afi, who’d started his way to the forest floor. Afi threw a teasing wave, the kind that said he’d have no need of young whelps, and continued on his way down.

The treetop seemed very quiet when he disappeared into the foliage below.

***

Four days in, and Ayden’s little nest had become quite cozy. Below, the greenwood rangers grew ever more restless, their nerves scraped raw under the constant barrage of the Call. They worked hard to conceal it, Ayden credited them that: they whiled away the waiting with stick fights and patrols, blowpipe competitions for range and accuracy, and anxious bets on when the Surge would finally crest. Ayden sparred with them only once, for after he routed all challengers, none would face him again. Afterward, he ventured down only in short bursts to gather intelligence and food. The invitations to stay aground he ignored. The one trembling, brave request to join him in his blind he glared into a stuttered apology.

He probably enjoyed that more than he should have, but the chatter and bravado of novices a quarter his age frayed his patience more than even the Hunter’s Call could. Ella would have disapproved. Crack it, Ella would have presided over their silly contests and stroked their pride and soothed them with songs at night. He snorted at the idea, but he couldn’t quite erase the smile at the thought of his little sister.

So back into his blind he went, blissfully alone, watching Feral birds arc across the western sky when he detected a hint of deep familiarity above the wrong.

Ella?

Ella! What was she doing here?

In the face of his sudden urgency, the cedar branches bent and shifted beneath him, passing him to the ground in moments. Ella was waiting for him with a soft smile that belied—and nearly disarmed—his concern. Still, he gripped her by the shoulders and asked, “What’s wrong, sister? What brings you here? Is everything all right?”

She plucked his hands from her shoulders and held them in her own, shaking her head indulgently. “Always thinking the worst, Ayden.”

“For good reason,” he said, thinking on that other time she’d come to find him on patrol, nearly three centuries past, with the news of their father—

Ella poked him in the belly, and when he glared at her, she flashed him that cracking cheeky grin and asked, “The new rangers, how do you find them?”

“Young,” Ayden said.

She smiled as if expecting his rancor. “Do be patient with them, brother. No doubt they will learn much from you.”

“Yes,” he drawled, “perhaps in the next hundred years I might succeed in teaching them the value of silence, but I am not hopeful.” And speaking of silence . . . “You never answered my question. What brings you here?”

Ella straightened up. “Why, my love of you, of course.”

“I see. And the real reason?”

“I’m going to see Chaya.”

“What, now?” He gripped her shoulders, scarcely resisting the urge to shake her. “The Ferals are gathering; you’d be a fool to—”

She knocked his hands away. “They never hurt us, you know that.”

“But the humans are on high guard now, and they would hurt you.”

“Not Chaya,” Ella insisted, thrusting forward into his space. He wondered if she realized the challenge she was issuing. Probably not. “She’s my friend and I trust her.”

Ayden covered his eyes with his hands, held them there until she tugged them away.

“I am not blind nor a fool, thank you very much.” Her indignation gave way to sadness as she added, “The human I go to see is dying, not dangerous.”

“That is what mortals do, you kno—” Ella eschewed the usual belly poke for a halfhearted belly punch, cutting him off. He scowled at her. “Your presence won’t change a thing. Go home, Ella.”

He tried to turn her round, but she held her ground. “No.”

“Ella . . .”

“I said no, Ayden. I’ll not let her die alone.”

Ayden let loose an exasperated sigh. Wherever had she learned such stubbornness? He realized that short of binding her, he would not be able to stop her. Though he had to admit, that idea did have its merits . . .

She poked him in the belly again. “Stop that. It’s not for you to command me, brother. I am not one of your rangers, if you’ll recall.”

“Yes, how silly of me to have forgotten.” But in fairness, it seemed he had; she would go with or without his permission, so they might as well part on amicable terms. He offered her a resigned smile.

“I forgive you,” she said, perfectly grave, though a smile was twinkling in her eyes. She stood on her toes to kiss both his temples. Then she was gone, off at a trot toward the human-elven border as if ’twere perfectly harmless: nothing more than some scribbled line on a disused map.

“Come back before the Surge crests!” he called.

“I will,” she called back, not even bothering to turn her head.

“And don’t forget to mute your song!”

Her laughing response was a blast of notes so loud that every ranger in his seeing winced—she’d have blazed like the sun to a human’s eyes—but then she went virtually silent, and he trusted her to stay that way for the duration of her foolish excursion.

He watched her go until he could no longer discern her through the trees. As he turned back to his cedar, he saw where she’d been standing a single small flower, pink-petaled and perfect, reaching toward the sun. Just like Ella, he thought: always grasping for things she could never have.

***

Back in his perch, Ayden tracked Ella’s progress through the human lands with his farseer. Between the clamor of the Call, the forest song, and Ella’s deliberate muting, he’d expected to lose all sound of her, and was pleasantly surprised to discover himself attuned enough to track her all the way to her human’s house. He kept watching and listening even when she disappeared inside. From time to time she emerged—fetching water from the well or wood for the stove—a bright, distant figure in the powerful lens of his farseer. A farseer that, strictly speaking, should have been trained on the gathering Ferals . . . Ayden resisted the twinge of guilt between his shoulder blades and kept watching the village.

And for that he thanked the fallen gods in a great, panicked rush when he spotted a pack of human soldiers, spread out a league beyond the village and heading straight for it.

Only centuries’ experience with conquering battle rage held him back—and just barely—from hurling himself down the tree and into action. Instead, he readjusted his farseer with shaking fingers. Ten men at least, though from this distance ’twas difficult to discern one from the next. They were slinking through the far field, making faint ripples in the wheat, their steps slow and measured. But that worked to his advantage: he could try to head them off before they reached the village.

Of course, they might not be coming for Ella. The Ferals were on the prowl, after all, and the humans were responding in kind.

But if they were coming for her . . .

He mapped a quick path and memorized the landmarks, then scrambled down from branch to bowing branch. As soon as his feet struck the forest floor, he was racing toward the border and across it for the first time in over two hundred and fifty years.

Ayden ran as he’d never run before, the forest parting a trail before him. He stayed within its safety for as long as he could, but soon the trees thinned and made way for fields of wheat and soy. Before stepping out into the open, he spent precious moments calming his mind and clamping down upon his song until it faded to the softest of whispers; humans could not hear elfsong, but they perceived it as a soft illumination that would betray him. He despised the sensation of binding himself, and the world round him seemed somehow less, but ’twas nothing compared to the thought of a world without Ella.

Even muted, he still possessed the use of all his hearing, and he cast out his senses in search of the soldiers as he sprinted across the fields. He found excitement, eagerness, hatred and anger, confidence and a touch of fear: men on the hunt for a dangerous trophy. Ayden bared his teeth. They had no idea how dangerous their hunt had just become.

He reached the muddy outskirts of the village and slowed to a stop amongst a copse of apple trees near the human’s home. Ella’s song was wrapped round the dying human’s like a swaddling blanket, soothing even to Ayden, though he dared not let it calm him. Instead he cast out his senses once more, his blood rising in his veins as he noted how close the soldiers had come. Too late to head them off, and no time to warn Ella without exposing them both. But surely she’d sensed him by now, and could hear his fear.

Hide, he thought. She might hear it and understand.

Then the time for thoughts was over.

He climbed the tallest tree in the orchard, a measly ten paces to the top, and braced himself to balance without his hands. Through his farseer he spotted the soldiers a hundred paces off, moving quietly down the dirt road. Closer now, he counted nineteen men.

He grabbed a fistful of darts—the lethal ones, not the sleepers—dropped one into his blowpipe, and put it to his lips. Eighty paces. He begged the tree for all he was worth to hide him well, for once the soldiers spotted him, he would lose his main advantage. The leaves and branches rustled softly, closing him in.

Sixty paces.

Fifty.

Ayden blew the first dart, aiming for the rear line in the hope that the soldiers ahead wouldn’t notice. The man slapped a hand to his neck, and Ayden planted darts in two more soldiers before the first one even hit the ground. A fourth soldier folded a second later, but then a cry went up and the whole contingent crouched behind their shields, shouting amongst themselves to find the marksman. Ayden took out two more before a sharp-eyed soldier spotted his perch, and before he could reload again, a hail of crossbow bolts chased him from the tree.

Discovered now, he unleashed his bound song with a satisfied growl and called up a fierce gust of wind, but the bolts were too fast and heavy to be swayed much. One skimmed his left arm as he ducked behind the trunk, ripping a burning furrow into his flesh.

He heard shouts of “Elf!” and “Get him!” and “Watch out, sorcery!” as he dumped his kit and jumped to the ground, wondering how by the fallen gods he would best thirteen men armed with crossbows now that he’d been seen. He sang to the wind for a greater gale and it complied, kicking up pebbles and debris and hurling them in violent spirals.

The soldiers shouted in fear and huddled behind their shields again. But this parlor trick wouldn’t hold them at bay for long; he needed to act quickly before they flanked him.

Storm, he thought. He’d show them a real storm.

As another salvo of bolts thunked against the tree that sheltered him, Ayden sucked in a breath and sought out every sizzling, snapping note in the air around him, in the dirt at his feet and even within his own body. He summoned them together into a tight, sparking ball of sharp notes and frantic tempos and hurled it at the soldiers.

Panicked screams, then shrieks as his ball lightning burst through the front soldier in a crackling fit of fire and smoke, arced off to a second and a third, regrouped and attacked a fourth. Ayden fought for all he was worth to hold it together, but he couldn’t stop it from flowing through the fifth man’s feet and into the dirt.

Six dead from his darts, five from his lightning; that left eight more between Ella and safety. He sang out to summon a second ball, and two soldiers turned tail and fled. But the remaining six found their courage and charged him.

His lightning was building too slowly. Desperate, Ayden pulled his daggers and threw, felling the two men in the lead from ten paces out.

He was running out of weapons. He whipped up the airsong round him into a smoldering crescendo, too hot for the humans to press through. Their fear screeched like untuned strings in the music of the battle as they fell back again. The grass round him caught fire, and he let it burn as he struggled to call together the charged notes once more.

A second ball lightning coalesced in his hands and surged forward with a clap of thunder, stopping the heart of the soldier it hit. Ayden urged it on, but his mind-voice cracked and the lightning went directly to ground.

He had no strength left in him to form a third. His legs buckled beneath him and his vision swam, but even as his knees hit the ground, his hands found a dead branch and snapped it in two—he’d dropped his fighting sticks with his kit, so these would have to do. His left arm throbbed where the bolt had grazed it, and his hand was slick with blood, but he had nearly eight centuries of practice on these vermin and if he could just . . . get . . . up . . . he knew he could take on the three who remained.

He was just getting one foot beneath him when something sharp slammed into his back. It knocked him face down into the dirt, ripped the air from his lungs. His first thought, before the pain hit, was of Ella; he prayed like he’d not prayed in over two hundred years that he’d bought her enough time to reach safety. His last thought, before the world went black, was that he’d miscalculated: there had been twenty men, not nineteen, and he’d overlooked the one who had scouted ahead.

Chapter 2

Not for the first time this week, Freyrík wished his brother were here. Well, not right here, right now, in his bedchambers with—

“Oh, Highness!” Lord Jafri threw his head back, planted his palms on Freyrík’s belly and sped his rocking across Freyrík’s hips. He was lovely, Freyrík had to admit, with those dark round eyes and black hair, bronze skin slick with sweat, sculpted arms trembling with exertion . . .

Arms, Freyrík reflected, that had earned their beauty wielding the sword. Not even sons of Earls were spared from the Surge Wars. At least Jafri would command his own company this time—

“Just like that, Highness,” Jafri breathed.

Freyrík wanted to comply but didn’t know what that referred to, since Jafri was doing all the work. Oh, he wanted to want the man, to lose himself in the tight, eager body atop him and the silk sheets below. To forget, just for a moment, the darkness and death encroaching upon his people. Only in scattered skirmishes yet, but not for long—he would have to mobilize the army soon. And as if that weren’t trouble enough, the contingent in Akrar had captured an elven spy, though not before the creature had single-handedly killed four-fifths of them. His men could barely hold one front against the darkers; if elvenkind meant to rekindle aggressions, Farr Province might not survi—

“Highness?”

Freyrík snapped back to the present and realized that Lord Jafri was staring down at him, worry pulling at his lips and creasing his forehead. He’d stopped moving. Freyrík’s member had gone limp inside him.

“Are you well, Your Highness?” One hand slid up Freyrík’s chest and settled hesitantly over his heart. “Is it . . . have I displeased you?”

Freyrík sighed and curled his hand over Lord Jafri’s, giving it a gentle squeeze. “Of course not,” he said. Then, because he could ill afford to worry about the easily-wounded feelings of someone who’d given their arrangement more meaning than it

ISBN: 978-1-937551-19-3

Release Date: 12/12/2011

Price: $4.99