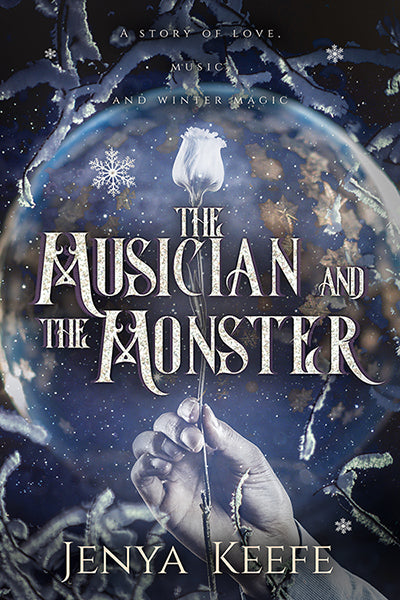

The Musician and the Monster

Hatred is a spell only true love can break.

Ángel Cruz is a dedicated session musician, until loyalty to his estranged family forces him to work for Oberon: the feared and hated envoy from the Otherworld. Overnight, Ángel is taken from his life, his friends, his work, and trapped in a hideous mansion in the middle of nowhere, under constant surveillance, and with only the frightening fae for company.

Oberon’s poor understanding of humans combined with Ángel’s resentment and loneliness threaten to cause real harm to the pair. Then a long winter together in the mansion unites them in their love of music. Slowly, Ángel’s anger thaws, and he begins to realize that Oberon feels alone too.

Gradually, these two souls from different worlds form a connection like none other. But hate and prejudice are powerful things, and it’ll take all the magic of their love to stop the wider world from forcing them apart.

This title comes with no special warnings.

Caution: The following details may be considered spoilerish. Click on a label to reveal its content.

Heat Wave: 4 - On-screen and mildly explicit love scenes

Erotic Frequency: 3 - Moderate

Genre: fantasy, magical realism, romance, urban fantasy / paranormal

Orientation: bisexual / pansexual, gay, queer

Tone: exciting, humorous, sweet

Themes: abduction/kidnapping/hostage (actual), celebrity / fame, enemies to lovers, gender expression, homophobia / transphobia, hurt / comfort, interspecies, power imbalance, trust issues

Kinks: barebacking, dirty talk, masturbation, size, voyeurism

Settings: Atlanta, Florida, Idaho, Jacksonville, mansion, Montana

Careers: adventurer / explorer / treasure hunter, musician, podcaster / YouTuber

Chapter One

“You’re selling me to the elf-lord?”

This house, the one Ángel Cruz had grown up in, looked exactly the same as always. A small, old house in Jacksonville, it was shaded by the serpentine branches of oaks and had last been decorated in the early 1980s. It was immaculately clean and redolent with Ángel’s childhood memories.

But nothing was the same, not after the bomb his father had just dropped.

Both his father and mother were present, which was alarming enough. Ángel hadn’t seen Victor Cruz and Abigail Barrington in the same room together since his high school graduation. And then there was the stranger—a red-haired white man—occupying Victor’s chair at the head of the dining room table. Victor never ceded that chair to anyone.

And for a third—they were selling him to the elf-lord. Ángel was dumbfounded.

“Don’t be melodramatic, Ángel.” Victor could have patented that sigh, the one that said, Why is my son always so tiring? “Sit down.”

Ángel sank into a chair. He’d been summoned up from his apartment in Miami for an emergency family meeting this morning. After his grueling six-hour drive he was sweaty, smelly, and tired.

He caught the red-haired man glancing between him and his father. People often did because they looked so much alike: both small-boned, skinny, and brown. Nervously Ángel toyed with the woven rainbow bracelet on his wrist, guitar-string calluses catching in the threads.

He’d been prepared for a confrontation, but there was no way he could have prepared for this.

Victor said, “This is simple. Your family has generously supported you for your entire life. You have been provided with the best of everything, including an excellent education that you decided to throw away. You chose to waste all your opportunities and live like a child. Now your family has money troubles, and for the first time, you’re being asked to contribute a little.”

“Money troubles?” Ángel glanced at the man who sat in his father’s chair, and then back to his father. “What does the elf-lord want with me?”

“He prefers not to be called the elf-lord,” said the stranger, fussing with the cuffs of his good gray suit. “He is the cultural envoy from the Otherworld.” At Ángel’s baffled stare, he added, “My name is Neil Jeremy. I’m a senior special agent with the Department of Otherworld Relations. The envoy is not fond of the term ‘elf’ in general. He prefers ‘fae.’”

Ángel nodded.

“The trouble,” continued Agent Jeremy, casting a scalpel-sharp glance at Victor, “is that Mr. Cruz has been indicted for attempting to run a Ponzi scheme on the cultural envoy from the Otherworld, and is now facing a prison term of up to fourteen years, not to mention liquidation of all assets to partly recompense the losses of his victims.”

Ángel stared at him. Then he looked at his father, who didn’t meet his eyes. “Excuse me?” Ángel said.

Agent Jeremy explained, tersely, that the FBI had been gathering evidence on Ángel’s father’s financial crimes for quite some time. A few months ago, Victor had contacted the envoy from the Otherworld with promises of extraordinary returns on a risk-free investment, and the envoy, apparently not an idiot, had alerted the DOR.

And now here they were.

The DOR agent said, “The envoy pledges that he will personally contribute ten million dollars in restitution to the other victims of your father, and the most serious charges against him will be dropped, if you, Ángel, are willing to live with and work for the envoy for six years.”

Ángel reeled back in his chair.

His father, a crook? It was inconceivable. Sure, Victor Cruz was a proud man, and sometimes a bitter one. He could be bad-tempered and judgmental. His divorce had dealt a blow to his pride that he’d never recovered from, and certainly his son’s open homosexuality had not brought him joy. But he lived by the immigrant’s ethic: hard work, education, Church, and family. Take faithful care of those, and the American Dream would fall into your hands. It had never occurred to Ángel that Victor might be dishonest.

“Ten million dollars?” Ángel’s voice squeaked when he was finally able to speak.

Jeremy said calmly, “Your father stole over seventeen million dollars from over thirty different investors.”

Ángel glanced around the room. The house was nice—everything worked perfectly, his father made sure of that—but no one had poured seventeen million dollars into this house.

Victor said tiredly, “Just cooperate, Ángel.”

“What would the el— What would the envoy want me to do?”

“The fae live communally, in large groups of family and friends,” said Jeremy. “As the only fae on Earth, the envoy is—well, he’s lonely. He doesn’t have anyone to talk to. You would be his companion. There would be a salary, of course, and room and board.”

The silence in the room was deafening.

After a moment, Ángel said, “He’s paying ten million dollars for company? Is he angry? Will he— Is he going to punish me for what my father did?”

Victor scoffed. “Now you are being absurd. The envoy is a man of honor.”

“Perfect target for a thief, then, no?” flashed Ángel at him. “Absurd was you trying to rip him off. And now you want me to save your ass.”

Agent Jeremy said blandly, “Six years is less than half the minimum prison sentence your father could expect for fraud.”

“I’m not the one who committed fraud,” said Ángel, standing up.

“Ángel,” said his mother. “Please sit.”

He looked at her. Abigail Barrington had married a short Cubano electrician in a burst of adolescent rebellion, and then, thinking better of it, had divorced him and moved back to Savannah, leaving her son behind. She looked out of place here in her ex-husband’s Jacksonville home—pale and blond and slim.

He sat.

He’d spent summers with her other family in Georgia, where he’d always felt, at best, like a guest; at worst, an embarrassing reminder of an episode everyone would prefer to forget. But he did remember happy times too. She had taught him to dance in the dining room of her house. They’d pushed the table and chairs up against the wall and turned up the radio to waltz to “She’s Always a Woman” by Billy Joel. She’d laughed as they danced.

She wasn’t laughing now. “No matter what you do, your father is going bankrupt. His business is gone. He’s going to lose this house, and his retirement account, and the money he put aside for you. He’ll be publicly disgraced before all his friends. He’ll lose friends, the people who trusted him.”

This was horrifying. In spite of himself, pity for his father rose up in his throat. He still couldn’t believe that Victor would ever do this—his father wouldn’t know how to contact the envoy from the Otherworld.

But he bet his wheeler-dealer stepfather would. “Did you know?” he asked. “Were you in on it too?”

“But if you step in,” she went on, not answering him, “that’s where the damage stops. Your father won’t go to prison. They won’t come after my family, or your brothers. Ned won’t lose his home, Michael will be able to stay in school—he’ll need to get loans, but he’ll be able to do it. Think of Ned and Michael. Think about Ned’s children.”

“You did know.” He stared at his mother. “I bet it was Bill’s thing all along, wasn’t it?”

“That doesn’t matter now.”

God. His mother was married to a man named Bill Harrington, who’d made bank in Hilton Head real estate development, who talked big about money and deals and how you had to spend in order to make. Maybe he’d lost his shirt. Maybe that’s where the seventeen million had gone: into Barrington’s pockets. Rescuing his ex-wife from her husband’s financial disaster—that would appeal to Victor. But then someone had gotten stupid, gotten caught, had brought them all down. “Doesn’t it? I might pay for Papá’s fuckup, but I’m not going to pay for Bill’s.”

Agent Jeremy said, “Bill Harrington hasn’t been indicted for these crimes. The evidence points to Victor Cruz.”

His mother twisted the knife. “It’s not as though you have a career or a family of your own.”

I do. Ángel didn’t say it out loud though, just stared at her, seeing only the lack of love in her blue eyes.

His father loved him in his way, or had once. When Ángel was outed at seventeen, Victor had raged, wept, begged him to pray for forgiveness and change his ways. But his mother had simply turned away, with a coolness that suggested she never had loved him. Whatever happy memories she cherished from his childhood weren’t happy enough for her to keep in touch.

He had defied them both. He hadn’t changed his ways. He’d quit college to make a living as a musician. He would rather play and sing for los turistas at the Manatee Bar in Ormond Beach than pursue a career in engineering or medicine, like his brothers, or to become an electrician and work for his father.

He’d somehow cherished the hope that his parents still loved him. That they would someday come to accept him. Their queer boy, their session musician.

Now those hopes tasted as bitter as aspirin dissolving on his tongue. This was his parents’ assessment of his actual worth. His life, his relationships, the career that he’d been building, held nothing of value to them. He was expendable, and they’d sacrifice him to save themselves.

But he couldn’t just abandon them.

He turned to the Agent Jeremy. “Two years.”

“Four,” said Jeremy instantly.

Ángel sighed, looking again at his family: his mother, blonde, with her family’s sky-blue eyes, so lacking in warmth. His father like an older mirror image, brown and lean.

Neither of them quite met his eyes.

“Done,” said Ángel.

An imperceptible sigh of relief from his parents. Maybe from Agent Jeremy too. Then his father said gruffly, “Thank you, retaco.”

“You haven’t called me retaco since I was seventeen,” he snapped. “You don’t go back now.” He transferred his glare to Agent Jeremy. “Four years. And after this, all debts are paid. We are done and done.”

Agent Jeremy snapped open his briefcase and pulled out a fat contract. "Have a look," he said, passing it across the table. "Let me know if there's anything else that you'd like us to change." Ángel began to read, heart breaking, eyes burning. He vowed that he would never return to this house, or speak to these people, ever again.

Chapter Two

“So is he dangerous?” Ángel asked Neil Jeremy.

They were in a helicopter, high over the mountains in northern Montana, speaking through noise-canceling headsets.

“No, don’t be silly,” said Jeremy.

Legends told that the fae were very dangerous: amoral, pitiless monsters, to be feared and placated and, above all, avoided. One absolutely did not voluntarily go live with them.

Ángel had heard the elf-lord’s music, of course. He’d released several albums: fae music transcribed for piano and orchestra. It was wild, incomprehensible music, full of strange harmonies and eerie, unearthly sounds. Ángel didn’t understand it, but it was enormously influential. In fact, most of what he knew about modern-day elves came from the lyrics and websites of elf-obsessed alt-metal musicians. Which seemed to justify Victor’s comments about Ángel’s squandered educational opportunities, but anyway.

Once, centuries before the birth of Christ, the beautiful and strange people of the Otherworld had moved freely across the magical veil. Then, for reasons that only the fae could know, that veil had become an impenetrable wall, and the fae had disappeared from the Earth, leaving behind only myths and tales: Tuatha de Danann. Daoine Sidhe. Tylwyth Teg. Fairies and djinni and demons; the peri, the yōkai, the Seelie and Unseelie Court. Monsters of all sorts.

The tales said that they lured people into bogs to drown, lured ships onto rocks to be destroyed. Stole people’s money and replaced it with autumn leaves, stole people’s babies and replaced them with monsters. Seduced people with their beauty, cursed them with their magic.

“Why did he come here?” he asked Jeremy.

“Stop worrying, Ángel. You won’t be in any danger.”

Jeremy had an annoying way of not really answering questions.

Sometime in the twentieth century—so Ángel had read—the veil had thinned enough for the fae of the Otherworld to begin studying humans. Watching them in magical ways, learning their languages, studying their culture.

Then, four years before Ángel was born, the fae had sent a gift through the veil. A previously ordinary beech tree in Springvale Park in Atlanta had begun to glow and emit an intoxicating scent. Crowds had gathered around, drawn as if by magic to the shining tree; then a rift had opened up, revealing a wooden chest full of objects that had been immediately taken into custody by the federal government.

The chest had contained several discs—exactly the same technology as vinyl phonograph records, although in a kind of clear, organic resinous material that Earth didn’t have. Someone had had to reverse-engineer a player that spun the discs at the right speed. The message on the discs had been in four languages: English, Mandarin Chinese, Hindi, and Arabic, all correct and fluent. They had promised that the people of the Otherworld meant humans no harm. The fae claimed to be scholars and artists, not warriors. They wanted to learn.

The box had also contained beautiful textiles and carvings; plant specimens that had gone straight to biologists for analysis, but which (it turned out) had been intended as food; jars of liquids—perfumes, ointments?—that chemists around the world were still trying to figure out; and more of that haunting music.

Entirely new fields of study had sprung up across the globe, just from the contents of that chest. The United States had established a new Department of Otherworld Relations.

And then, eight years ago, another tree had begun to glow: a crepe myrtle on the Georgia Tech campus. And an elf-lord had stepped from its branches. Alone, naked but for blush-colored crepe myrtle blossoms, and the veil of his long hair.

The elf-lord had been arrested by freaked-out campus police before the DOR had swooped in and established him in a new position: cultural envoy. Since then, Ángel had seen pictures of him on the internet and in magazines. He was tall, humanoid, fluent in English. He was a musician. He said he was a scholar. He only wanted to live on Earth and exchange information. He sometimes gave concerts and little talks about the Otherworld, or at least he used to; Ángel couldn’t remember the last one. He was pretty sure that he’d consulted with the scholars who were trying to understand the gifts that had been sent. For a while he had been a frequent guest at the White House. He’d once played a piano recital at a state dinner for the British Prime Minister and his family. Chopin.

Ángel stared out at the strange landscape beneath him. “If he’s lonely,” he persisted, “why doesn’t another elf come through to be with him? Or why doesn’t he just go back home?”

“The veil doesn’t work that way. Well—we don’t actually know how it works. But he says no one else can come through. It was just that one time.”

“And you believe him? Maybe there are other elves in, like, Africa, or China, and we just don’t know about it.”

“We would know,” said Jeremy.

Ángel wasn’t convinced. The elves were tricksters—everyone said so. It was in supermarket tabloids and Facebook memes, in newspaper editorials and Twitter posts. People discussed “the alien problem” on Fox News and MSNBC. Some were terrified that the envoy was luring humanity into a false sense of security with his apparently harmless ways, the harbinger of a magical invasion. In eight years the invasion had failed to materialize, though. As far as Ángel knew, the envoy was nothing but a piano player.

The only other thing Ángel really knew about the cultural envoy from the Otherworld was that he always seemed to wear exactly the same outfit: crisp black button-down shirts tucked into tailored black pants, polished black leather shoes. “Like he’s trying to be as boring as possible,” Ángel’s best friend Marissa had said. “Like an elf-lord could ever blend in.”

Down below the helicopter’s curved window, an endless deserted vista of mountains flowed by under a sunlit blue sky. He had assumed that the envoy to the Otherworld lived in or near the Department of Otherworld Relations headquarters in Atlanta, so he had been surprised, this morning, when the DOR jet had taken him nonstop from Miami to Missoula, Montana. From there they’d boarded this helicopter and flown north. They were now somewhere up near Canada, and Ángel couldn’t have felt farther from home if they’d been on the moon.

There was nothing down there. Nothing but huge mountains and deep valleys and cliffs and rocks and trees, and streams like shining steel guitar strings, and occasional narrow, winding roads with no cars on them.

Who knew there were parts of the country that were this remote? Ángel shivered and wondered if it ever snowed up here. Did the envoy from the Otherworld like it? Did the Otherworld have mountains? Did it snow there?

“Look up ahead,” said Agent Jeremy’s voice in his headset, and Ángel followed his pointing finger to see a large grassy hill in a valley, cleared of trees, with a tall wall around it and a large pink house in the middle.

The DOR agent said, “The house was built by a software tycoon in the nineties. I guess he thought it was picturesque up here. Didn’t take long before he realized he didn’t want to live in the middle of nowhere after all, and moved back to California. He donated it and all its furnishings to the DOR.”

“Does the envoy like living in the middle of nowhere?” asked Ángel.

“It’s very secure,” said Jeremy. “You’re one of about twenty people in the world who knows where the envoy lives. The locals think a reclusive novelist lives here. If you tell anyone, we will be annoyed.”

“Oh.”

As they got closer, it became clear that the house was in fact a mansion, very ornate, faced with some sort of gleaming salmon-colored stone, with white fluted columns, round-topped windows, and curving balconies. Ángel’s mind groped through the lessons of a half-forgotten undergraduate architecture class, and came up with “plantation/rococo” to describe the style.

The mansion was encircled by a rolling lawn, late-summer brown, which was protected by a high spike-topped cinder block wall, which was surrounded by miles and miles and miles of dense forest, dark green under aching blue skies. In the distance stood ranks of purple-and-white mountains. The helicopter lowered itself toward a concrete pad just outside the wall, where an octagonal pink mini-mansion guarded the gates. “The security detail lives here at the gatehouse,” said the DOR agent. “No one lives in the main house except Oberon, and now you. Nearest town is Stahlberg, about twenty-five miles away.”

“Is he really called Oberon? I thought that was made up by the press.”

“Oh no, that’s his name.”

Ángel glanced at Jeremy, eyebrows raised. “Yeah? ‘I know a bank where the wild thyme blows’ Oberon?”

“No, of course not. No one can actually pronounce his real name. He accepts ‘Oberon’ as a reasonable substitute. Here you go.”

The helicopter touched down. Ángel took off the headset, gathered up his backpack and guitar, and hopped down onto the concrete pad, instinctively cowering away from the deafening concussion of the still-spinning rotors. He glanced back through his blowing hair and saw that the DOR agent had not followed him.

Ángel stood alone as the helicopter leaped skyward. Agent Jeremy gave him a little wave. Ángel swallowed, his mouth dry, watching the helicopter dwindle into the distance.

He walked across the grass to the gatehouse. Waiting there was a young woman in a professional-looking navy pantsuit. She was tall and straight, and carried herself with a competent air that spoke of the military. Her black hair was pulled back in a sleek ponytail. She did not smile when she greeted him.

“Ángel Cruz. I’m Chandler Evanston of the DOR, chief of the envoy’s security. Please put your bags, shoes, and the contents of your pockets in this bin, and step through the metal detector.”

Evanston oversaw a staff of navy-suited goons who apparently weren’t content to let the metal detector do its job. They searched his backpack and guitar case, poking a sort of periscope inside the instrument’s sound hole to view its interior. Ángel thought that was funny until they turned their attention to him, patting him down with alarming thoroughness, checking inside his mouth, running fingers through his hair and behind his ears, and impersonally exploring his crotch through his jeans. When they discovered his cell phone tucked into his sock, the chief of security frowned. “You were told no computers.”

“It’s just my phone,” he protested.

“No computers.” She pocketed it. “Did you disobey instructions in any other way?”

“Will I get that back?”

“No,” she said, glaring at him. “Strip.”

“What?”

“Strip, or we’ll strip you.”

He stripped. A goon rotated him by the shoulders and bent him over a table. “Gonna do a cavity search, guapo?” asked Ángel, his voice high and trembling despite his bravado. “Hope you got some lube.”

The goon let go without probing further. “He’s clean.”

“That wouldn’t have been necessary if you hadn’t demonstrated your willingness to disobey instructions,” said Evanston, handing him his clothes.

“So it was punishment, not security,” gritted Ángel, still shaking as he pulled his jeans up over his hips. “Got it.”

“I don’t think you do,” she said. “Mr. Cruz, have a look at this.”

He pulled his T-shirt over his head as she turned on a TV. She showed him footage of a large crowd of angry people, assembled in front of a bank of skyscrapers. There must have been five hundred people there, chanting angrily but incomprehensibly, waving homemade magic-marker signs that said things like SAVE OUR SPECIES and HUMANS FIRST.

“This was last week,” said Evanston. “On the eighth anniversary of Oberon’s arrival. Chicago.” She pushed a button on the remote. “This one’s in Dallas.” A protester waved a sign that said DEATH TO MONSTERS.

“Las Vegas.” The signs read GOD HATES ELVES and KILL THE ELF-LORD. A brick sailed over the heads of an array of cops and bounced impotently off the gleaming surface of the Luxor Casino.

“Since Oberon’s arrival eight years ago, there have been thirteen credible assassination attempts,” continued Evanston. “He has been poisoned, shot at, and targeted by explosive-bearing drones. He has been injured four times, once quite seriously. Just last April a bullet missed his head by about six inches when he was in New York for a UN meeting.”

“Right,” said Ángel, tugging his hair out from the collar of his shirt. “That’s really scary. But it doesn’t have anything to do with me. I didn’t seek out this position. He asked for me to come.”

“I know,” she said. “He was determined to bring you here. I advised against it. My job is to keep him safe. I do that by controlling every aspect of his environment, and that includes you.”

“Well, good to know where I stand,” sneered Ángel. “Can I have my phone back?”

“No. You cannot have your phone back. From now on, any communication you make with anyone outside this estate will go through me.”

“But—”

“No buts. You signed a contract in which you agreed to submit to any and all measures deemed appropriate by the envoy’s security staff. Learn to live with it, Mr. Cruz. And don’t lie to me again—you’ll find I don’t like liars. Gather your stuff and my men will take you up to the house. Oberon is waiting for you.”

Chapter Three

Two of the goons walked with him out across the dry lawn toward the house. They were brawny and fit in their navy suits. They might be carrying guns.

In the distance, at the top of the hill, the tall form of the cultural envoy from the Otherworld stood silhouetted against the sky, his black clothes and famous white-and-green-streaked hair fluttering a little in the breeze. Ángel took a long, shuddering breath of cool mountain air.

The goons exchanged a glance and stopped. Ángel stopped with them.

“Go on,” said one of them, waving him on.

“Aren’t you coming?”

“Oberon will take care of you,” said the same goon, with fake heartiness. He waved a hand in greeting to the distant envoy. “Go on. Call us if you need anything.”

Ángel swallowed and kept walking.

Behind him, he heard the other goon mutter, “Better him than me.”

“Me too. Damn, it gives me the willies.”

“Fuck me,” whispered Ángel.

He was on. He could do this. He forced his feet to move, kept his chin high, his shoulders loose. Pretended he was stepping onto a stage. Giving a performance. He looked taller when he was performing.

He met his audience on the brow of the hill.

The elf-lord said, “Good afternoon, Ángel Cruz. Welcome to my home. I am Oberon. Am I pronouncing your name correctly?”

“Yes,” said Ángel. No sound came out. He cleared his throat and tried again. “Yes.”

“May I carry your guitar?” The elf extended a languid hand.

“Oh. Yes, thanks.” Ángel was very careful not to touch Oberon as he gave him the guitar case.

Side by side, they walked back toward the pink mansion.

He felt like a rabbit taking a stroll with an Alaskan malamute. His blood was rushing with adrenaline, his mouth dry, heart thumping. Sweat pooled in the small of his back, ran coldly down his temples to his jaw. He had to force himself to take each step forward, to not break and flee back to the gatehouse, to beg Chandler Evanston and the goons to protect him.

Just stay cool, Ángel.

He kept his eyes forward, but examined Oberon with his peripheral vision.

In photographs—and on the internet, and on the cover of his bestselling album Fae Seasonal Song-Cycles—the cultural envoy from the Otherworld appeared, essentially, to be a man: a strange man, with a serious, high-boned face. A tall and slim man, with large eyes, pale skin and hair, clad in black. Accounts of his first appearance from the tree said he’d had long hair, but it was short in every picture Ángel had ever seen. He seemed odd, not normal, but not necessarily inhuman.

In person?

He was utterly, utterly inhuman. He didn’t look or sound or smell human. He was white and weird and frighteningly beautiful, more beautiful than any human. Now he glanced at Ángel, catching him studying him, and Ángel flinched, heart in his throat.

“This estate is very large,” Oberon said. “You will be comfortable here.”

His voice was deep, a velvety bass-baritone. It sounded inhuman too, as if the organ from which it emerged were different from a man’s larynx. He spoke slowly, but with an unimpeachable North American accent, more neutral than Ángel’s own Cuban-inflected English. His expression didn’t change as he spoke: it was impossible to imagine what thoughts or emotions were happening behind his shining green eyes. The curve of his wide mouth looked contemptuous. Or cruel.

He was a walking Uncanny Valley—almost human, but every tiny difference was just different enough to make Ángel’s scalp prickle.

What the fuck have I done?How am I going to live with this thing for four years?

They crossed a broad tiled patio, past an out-of-commission fountain of frolicking dolphins, toward the house’s porticoed front entrance. The house was sided in big sheets of pink-veined marble, like raw pork belly. It must have been ruinously expensive to ship all that stone up here. Above each roman-arched window was a circular white frieze, featuring a flying cupid in gilded bas-relief; above the door was a fan-shaped stained-glass window depicting a baroque angel, clothed only in her pink hair and surrounded by purple morning-glory flowers. Ángel mouthed a silent Wow.

They approached the house, Oberon moving with inhuman grace, turning a simple walk into the lazy stalk of a hunting cat, boneless and deadly. The big door was opened, as they approached, by a petite woman wearing jeans and an embroidered shirt. “Ángel Cruz,” said the envoy, “may I introduce Lily Va. She does the cooking and cleaning for us.” He gave her Ángel’s guitar.

She was human, middle-aged, Asian. Short and sturdy, a bit of silver in her black ponytail. He wanted to stare at her all day, rather than look at Oberon. She said, “I’m here every day. Let me know if there’s anything you need,” and reached for Ángel’s backpack.

He reluctantly surrendered it to her. “Thanks,” he said. “I will. Um, do you live here too?”

“No, sir, I live at the gatehouse. My husband works for the security team.”

“Oh, please don’t call me sir.”

Oberon said, “Tell Lily your food preferences, or if there is anything you don’t eat.”

Ángel nodded. Oberon and Lily stared at him expectantly. “Oh. Now? Um, no allergies. I don’t really like zucchini. Or veal, veal is gross. That’s all.”

“Good,” said Oberon. “Come, I’ll give you a tour of the house.”

He led the way, and Ángel followed, casting a longing glance back at Lily. She nodded at him gravely.

The house was decorated within an inch of its life in shades of pink, purple, and turquoise. The living room had a sectional sofa of dark-pink leather like sunburned skin. The sofa curved around a fieldstone fireplace large enough to roast an ox. A gigantic mural of mermaids and seahorses shone on the opposite wall. The dining room featured lavender paneling, a white lacquer and gilt table that seated twenty, and a mirrored chandelier the size of a Volkswagen Beetle. “I usually eat in the kitchen,” said Oberon.

The more Ángel saw of the big house, the more unreal it seemed. He associated elves with nature—they liked woods and forests and . . . natural fibers. Right? Surely the creatures that inspired everyone from Spenser to Tolkien wouldn’t live in this glossy kitsch mansion?

“Did you decorate?” he ventured.

“No, these are the original furnishings. I have changed almost nothing. It seems rather ornate to me. Do you agree?” Oberon turned to Ángel so suddenly that he nearly startled.

“It’s a little, yes,” he stammered.

“Here is the music room. I know you are a musician.” Oberon gestured with a liquid hand around the small, surprisingly cozy room with a piano, an electric organ, and several other instruments. “It has the best acoustics in the house. It’s a good place to play or sing. And my office is through here.”

The office was someone’s dream of manly power: dark wood paneling, a huge mahogany desk like an altar, flanked by big burgundy leather wingback armchairs.

One object stood out: a big plain ceramic pot by the window, in which grew a plant: glossy dark-green leaves, sturdy thorny stems bearing silver-white roses. Ángel had never seen a rose bush indoors.

“That didn’t come with the house,” he guessed.

“No, the roses came from home. I spend most of my days here in the office. You’re welcome to join me anytime.”

Ángel risked a sidelong glance at the envoy’s inscrutable face. God. He imagined himself hanging out here while Oberon worked, and suppressed a shiver.

Oberon must have seen it. “You’re tired,” he said. “I’ll show you your room; you can rest before dinner.”

To be alone, away from the envoy, for a little while. The idea almost made Ángel light-headed with relief. “That would be nice.”

“First, though, you must see the security system.” Oberon crossed to a panel of monitors built into the wall. “Most rooms have one of these terminals,” he said, pushing a button. A live video image of the living room appeared: empty fireplace, pink sofa. “Push this to scroll through the feeds.” He flipped through

Word Count: 80000

Page Count: ~300

Cover By: Shayne Leighton

ISBN: 978-1-62649-886-0

Release Date: 09/30/2019

Price: $4.99