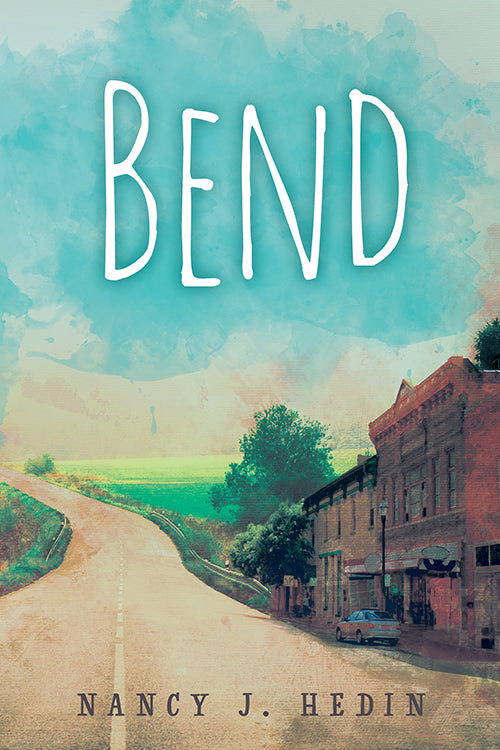

Bend

Lorraine Tyler is the only queer person in Bend, Minnesota. Or at least that’s what it feels like when the local church preaches so sternly against homosexuality. Which is why she’s fighting so hard to win the McGerber scholarship—her ticket out of Bend—even though her biggest competition is her twin sister, Becky. And even though she’s got no real hope—not with the scholarship’s morality clause and that one time she kissed the preacher’s daughter.

Everything changes when a new girl comes to town. Charity is mysterious, passionate, and—to Lorraine’s delighted surprise—queer too. Now Lorraine may have a chance at freedom and real love.

But then Becky disappears, and Lorraine uncovers an old, painful secret that could tear the family apart. They need each other more than ever now, and somehow it’s Lorraine—the sinner, the black sheep—who holds the power to bring them together. But only if she herself can learn to bend.

- Winner: 2018 Goldie Awards - Debut novel

- Finalist: 2018 GCLS Awards - Debut Novel and General Fiction

- Finalist: 2017 INDIES - LGBT (Adult Fiction)

- Finalist: 2017 INDIES - Young Adult Fiction

Reader discretion advised. This title contains the following sensitive themes:

self-harm

Caution: The following details may be considered spoilerish. Click on a label to reveal its content.

Heat Wave: 4 - On-screen and mildly explicit love scenes

Erotic Frequency: 2 - Not many

Themes: abuse, acceptance, coming of age, coming out, death / the afterlife, family, first love, first time, fitting in, homophobia / transphobia, illness / injury, mental illness

CHAPTER ONE

The Call

It was early morning on a Saturday, and my momma was waking up God. Since the night before, when Momma answered a phone call, she had been beseeching God as if she had him on retainer like a lawyer or on a leash like a dangerous dog.

I stayed in my room. I would have dressed in camouflage or armor if I had any. I didn’t.

“Lorraine.”

Christ, I cringed every time I heard her call my name. It reminded me of everything I hated about being seventeen years old, still in high school, and living in Bend, Minnesota. Why’d I have to be called such an old-fashioned name? For that matter, why were we living like we were some hicks from the Stone Age: no cell phone, no cable TV, and no internet? I was trapped everywhere I turned.

I went to slip through the window, but before I could get completely out of the house and truthfully say I didn’t hear her, Momma called me into the kitchen. She said I should explain what had possibly necessitated a call from the minister and a Saturday morning meeting about “your daughter.”

“That’s what he said to me, Lorraine: ‘your daughter.’ Who do you suppose he meant?”

“It could be Becky.” I said it, but I didn’t believe it for a damn minute. My twin sister, Becky, wouldn’t be the subject of a serious meeting with Pastor Grind unless somebody wanted to name her a saint, and I doubted the Church of Christ went in for saints. That was more of a Catholic thing.

My momma wasn’t Catholic, but she continued the inquisition anyway.

“What would people think to know I’ve been called in to Pastor Grind’s office? Do you think it’s about the scholarship? So help me God if your sister doesn’t win the McGerber scholarship, I’m going to raise holy hell.”

What about me winning the scholarship? That was what I wanted to say, but I didn’t. I was smart enough to win a scholarship and smart enough to know I shouldn’t suggest to my momma that anybody but her Becky would win it. It didn’t matter that I wanted the scholarship. It didn’t matter that I wanted out and needed out—out of reach of Momma; out of Bend, Minnesota; and just plain out.

I’d done what I could to earn college money. I saved every penny I made bussing tables at the diner where Momma worked. I raised chickens and rabbits and sold them. I worked with Benjamin “Twitch” Twitchell, my dad’s best friend and the local vet, when Momma would allow it. I had good grades and plans to study pre-veterinary medicine in college. The librarian had helped me apply, and I had already been accepted to an animal sciences program. I hadn’t told anybody. It was on a need-to-know basis, and nobody else needed to know. For that matter, the college didn’t know I didn’t have the money to go unless I won that scholarship, and no matter what Momma thought, I had a real shot at winning a scholarship.

Who’s in trouble with Pastor Grind? I wondered. Then I wondered, Who am I kidding? Becky never did anything wrong. I was in trouble, sure as hell, but which sin had Pastor Grind uncovered? I went outside our farmhouse and gave myself the most complete moral frisking I could muster.

Yes, I had sold my lunch ticket for cash. Yes, I resold candy and pop from my locker between classes. And yes, boys with too many chores and sports practices and too little time and intellect to complete biology worksheets and English compositions had paid me to do their homework. Although these were sins by the book, I doubted that any of that mattered to Pastor Grind. I dug deeper—examined my heart, soul, and hormones. Holy Christ, it had to be the kiss.

***

I paced east to west on the open front porch and pulled at the bill of my baseball cap like the pressure against the back of my head would give me a good idea. It didn’t. My dogs, Pants and Sniff, walked along beside me, their nails clicking on the floor boards. Why hadn’t I kept my lust in my heart where it belonged?

The screen door slammed, Becky making her typical entrance onto the front porch. She planted herself in the porch swing with her nose in a Good Housekeeping magazine. She set a Brides magazine beside her.

“Momma’s sure got her undies in a knot about something,” Becky said. “What’d you do now?”

“Shut up! What do you know about it?”

“I know that it was Pastor Grind on the phone,” Becky said. “I know that Pastor Grind will announce who wins the McGerber scholarship in May. And I know that the scholarship will go to the brightest, holiest student in Bend. We both know who that is, and it isn’t you.”

“You’re right. It’s probably Jolene Grind,” I said, knowing that the suggestion would irritate Becky.

“She’s smart, but her grades aren’t as good as mine,” Becky said. “That scholarship is mine. I’m going to win that scholarship and attend the Bible College in St. Paul.”

“You haven’t won it yet.”

I tried to sound confident, but I knew that Becky stood in the way of the biggest scholarship offered in Bend, Minnesota. The McGerber scholarship, named after its benefactor, J.C. McGerber, was supposed to be awarded to the graduating senior with the highest grades, but given that McGerber was a holier-than-though-pew-polishing-member of our church, he might just choose Becky anyway. After all, Becky was a member of BOCK—Brides of Christ’s Kingdom, a club for girls at our church. I had not been asked to join—not that I missed memorizing Bible verses, cooking hot dish for church socials, and knitting potholders for missionaries. What the hell did missionaries need with potholders anyway?

Becky and I had the highest grades in our class. Which of us had the fraction of a point higher, I wasn’t sure. I hoped that if we were tied, the competition would be settled by a wrestling match, but the way my luck ran it would be a spirituality contest or, worse yet, a beauty contest. Becky was blonde, beautiful, and built. It was like the geometry book was divided between us. She got all the curves, and I got the angles.

I was usually quick to remind Becky that I was born first. In Biblical terms we were the Jacob and Esau of Bend. I was the hairy firstborn fixated on animals, born every bit dark as Becky was light. My brown wild curls spiraled while Becky’s straight blonde tresses only curled at the ends. I expected to lose my birthright to my smoother, younger twin. Like the twins in the Old Testament story, we had competed since we were in the womb, and like the twins of the Old Testament, Momma favored the younger one.

The goal was college, but Momma didn’t offer a way to pay for that goal. We were just supposed to make it there somehow. Dad wasn’t any help either. He didn’t believe in student loans. He wouldn’t stand for them, and he wouldn’t sign for them. The winner of the scholarship went to college the next fall. The loser had to stay in Bend and work at the diner where Momma worked, until she had earned enough money to go to school or just given up on college and married somebody.

If Momma knew any more details about why Pastor Grind called, she didn’t tip her hand. It was like Momma tumbled the information over in her mind, polishing it like a rock. Eventually, she’d sling that stone at someone. I was prepared to duck.

Becky and I stayed busy on the front porch ignoring each other. Dad was in the barn finishing his farm chores before he left for whatever grunt construction job he’d hunted up to bring more money into our house. God, how I wished that phone had rung when only Dad had been in the house. He wouldn’t have answered it. He hated the phone. He said it was a noise contraption that interrupted the thinking time of good people. Furthermore, he said it was an obsession to a whole group of people who could sure benefit from some thinking time. But Dad hadn’t answered the phone. Momma had.

Then the peace was broken. Momma’s voice, like a shovel scraping against concrete, carried in the humid August air and filtered out the open windows. More prayers and curses. Her habit of praying and cussing had increased since the Bend congregation had hired Pastor Grind. Momma said she knew him from when she was a girl, and she liked his stand on sin. He was against it, and he defined it broadly. His list of for-certain sins, possible sins, and things a person shouldn’t even think was longer than either the Lutherans’ or the Catholics’. Momma had no time for Jesus, or as Momma called him, “the sissy god-man of the New Testament.” She said Jesus was God and all, and that we should follow his word in the New Testament, but he just wasn’t the man of action like the God in the Old Testament.

Momma’s God wore pants, and needed to shave several times a day to keep from having a swarthy five-o’clock-shadowed face. Her God threw jagged stones at transgressors and roasted unrepentant sinners in the fires of hell. She clung to the wrathful old timer of the Old Testament who ferreted out and punished sin the way some rogue cop from the movies punished crime.

The screen door slammed, and Momma rumbled out of the house. She wore her blue dress, her church dress.

“Crap!” I mumbled.

That dress was as much of a sign as a screaming siren or a green-tinted sky before a tornado. It confirmed what I suspected—someone was in big trouble. Momma inspected Becky and me, and then she scanned the yard over the top of her glasses. Our yard attracted junk like cat hair on stretch pants. The care of the yard was the only domain I knew of that Dad had not let Momma rule. It was a rare instance, but I remembered Dad using his firm voice when he’d once said, “Peggy, you promised that the yard was mine. I don’t fight you on nothing else, but the yard is mine.”

I knew Momma wouldn’t pardon Dad for the cluttered lawn he’d created. She wouldn’t excuse it. She would put it in a queue for her attention another time. To that end, she removed her dog-eared, spiral-bound notebook from her purse. Her personal pencil was secured to the spiral by a piece of string. At one time, the pencil had had the golden rule printed on it, but now had been used to the point that it just read: Do unto others. Momma pinched the pencil between her calloused fingers, licked the lead, made a note, slapped the notebook shut, and slid it into her purse. She soldiered down the steps toward the car. “Becky, darling. Keep an eye on that roast I put in the slow cooker.”

Momma didn’t trust Crock-Pots.

“Lorraine, you can run to the barn and tell your dad I have a meeting at church.”

Becky hoisted herself out of the porch swing and came to stand next to me, elbowed me, and we both trailed after Momma while spitting insults to each other under our breath.

“Pig.”

“Cow.”

“Idiot.”

“Moron.”

My stomach clenched like a fist. I thought about the scholarship and the kiss. My affliction compounded.

“Becky, tell your dad I’m going.” Momma looked directly at me. “You might as well come along. It’ll probably save me the trouble of repeating myself later. My guess, this meeting has something to do with you.”

Becky giggled. I choked.

“Momma, are you sure you don’t need me to drive you?” Becky called after Momma.

I rolled my eyes and discreetly flipped my middle finger at the suck-up asswipe.

“No, honey. I’ll be fine,” Momma called over her shoulder as she marched me to the family car.

Momma opened the driver’s-side door of our ancient blue-paneled station wagon, designed for family vacations, but sturdy enough for third-world invasions. Momma wedged herself behind the steering wheel, then clawed at the seat belt and negotiated it from that dark, hidden place below her left hip. Dust, hair, and candy wrappers stuck to the sides of her hand. I kept my fingers crossed that Momma would keep hold of the seat belt and not let it speed back to its burrow between the seat and door. She needed no extra aggravation. After Momma had stretched the strap to the last inch of fabric, she forced the silver tongue into the buckle and let it settle against her stomach. Click.

My breakfast of Oaty Loops scrambled up my throat like it was fleeing a burning building. Only the distraction and possible danger of Momma’s driving kept me from vomiting right then and there.

Backing down was impossible for Momma. Backing up wasn’t her strong suit either. Momma jerked the car backward six inches or a foot, then hit the brakes. After five rounds of this, she pressed harder on the gas pedal and the car sped backward until it hit the clothesline pole.

The clothesline pole brought the car to a full stop. Momma rubbed her neck and pounded her palms on the steering wheel. The whiplash must have knocked Momma’s original idea out of her head.

“Get out. Get out!” Momma yelled at me. “Just make sure I can find you when I get home.” She shifted the car into drive. I didn’t need a second invitation. I scampered out of the car. Momma weaved the car toward the blacktop. I stood by Becky.

“Cow.”

“Horse.”

“Puke.”

“Shithead.”

The faint smell of roast beef filtered out into the yard when Becky opened the door, entered, and returned again from checking the Crock-Pot. She turned to me. “What’s that crashing sound? Oh, that’s the sound of you bussing dirty plates at the diner for the rest of your life, Lorraine.”

“Becky, you don’t know me or what I am capable of.” God, I hoped I was right, because I didn’t want anyone knowing what I’d done.

CHAPTER TWO

The Kiss

In the heat of the August sunshine and impending doom of Momma and God’s wrath, I allowed myself to think briefly of the kiss. I hadn’t made one slip until the last week of school. I kissed her. I wanted to blame the slip up on the baseball team and fragrance-induced amnesia. The Bend Pioneers had defeated the pukes from Browerville for the conference championship. The whole school had been giddy. I’d been caught up in Pioneers fever when I’d entered the music practice room to work on my map of the Ottoman Empire with Jolene Grind.

The room usually smelled like valve oil and sweat, but that day it smelled like Jolene’s Baby Magic lotion and strawberry Lip Smacker. The flowery, fruity smells went right to that part of my brain that controlled memory. I completely forgot I wasn’t supposed to be queer. I wasn’t supposed to secretly love Jolene, and I sure as hell forgot I wasn’t supposed to kiss Jolene Grind, the daughter of Pastor Allister Grind.

But that kiss—how could anyone in their right mind find anything wrong with that kiss? When my lips touched Jolene’s cheek, a cheek cool and smooth like the belly of a minnow, I shuddered and said, “Mmm.”

When I opened my eyes, Jolene was staring at me like I had two heads and both of them were butt-ugly.

“What are you doing?” Jolene’s eyes widened and her face flushed. “Holy Sodom and Gomorrah, Lorraine! You want to put us both on the fast train to hell too?”

I hadn’t a clue what she meant by that, but I didn’t say anything.

She rummaged through her quilted book bag. “Here, you hold this.” Jolene handed me her Good News for Modern Man edition of the Bible. Then she grabbed it back again, stuffed it in her bag, and took my hands in hers. I loved her holding my hands, but it was obvious on Jolene’s face that she remembered all the things that I had forgotten. “I forgive you, Lorraine. I won’t tell anybody.”

Since the kiss, I had allowed myself several daydreams about how I would eventually live with Jolene Grind. Previously, I had lived off the crumbs of friendship, times when Jolene rested her head on my shoulder during long bus rides for field trips, times we cuddled close against the cold Minnesota air during late-season football games, and times when I sat by Jolene in the pew of the church where Jolene’s father preached damnation for all queers like me.

Why was it that boys had to have all the girls’ kisses for God to be happy? I didn’t want to kiss boys. I’d enjoyed football and baseball with them in their yards and at recess when I was in elementary school. I wanted to run faster, pass farther, and tackle harder than the boys, but I never wanted to kiss boys. I’d loved girls by first grade. I didn’t ask for the feelings to come, and they didn’t go away. Plenty of times over the past couple of years, Pastor Grind had said that if feelings like that didn’t go away, then the feeler of those feelings was going straight to hell.

Thoughts of hell burned my eyes, and tears dammed up as I looked at Jolene Grind. Even though I believed she wouldn’t tell, some of me wanted to rewind, erase what happened. I was seven parts scared and eight parts embarrassed. I only half listened while Jolene spoke, searching my brain for a suitable lie for what I’d done, if anyone ever found out. Would they believe there’d been a fly on Jolene’s cheek and I’d gently swatted it away with my lips?

“I’m so sorry, Jolene. I wasn’t thinking. Please don’t hate me.”

“Lorraine, I could never hate you. But you don’t know the problems your desires could make for everybody.”

Jolene cried. Seeing Jolene cry made my heart break all over again, and I hated myself for what I felt and the stupid mistake I’d made. Then I shuddered for a second time. A vision of Momma flashed in my mind. She was scowling at me, wearing her blue dress hiked up along her hips, because my mistake had staked her to a big wooden cross. I hated myself. Again.

Jolene said she would pray for my soul at church. I wanted to tell Jolene that my soul could wait. I wanted to tell Jolene to pray for my body to have a place to live if Momma found out I kissed a girl. I wanted to tell Jolene if prayer helped, Momma would have prayed me into liking boys and shoehorned me into dresses and patent leather shoes ever since she had read about me loving girls in my journal. The sneak.

I prayed too, but nothing changed. That’s what I wanted to scream at Jolene, but I didn’t. I stayed quiet and sorry.

After the kiss, the promises of prayers, and the remorse, Jolene gathered up her stuff, touched my shoulder, and said she would see me the next day at school. Jolene never mentioned the incident to me again. The school year ended. Summer came.

***

Now, a new school year was about to begin and still nothing had changed. I looked around the yard and at the cloud of dust Momma had left in her wake. I knew Momma hated me for being queer. Sure, she loved me some, but Momma worried more about my salvation than my happiness.

I knew Dad knew I was homosexual, because Momma wouldn’t have missed the opportunity to tell him. I wasn’t certain that Dad really cared that I was queer. He probably had an animal story that evidenced the necessity of aberrant pairings for the survival of the species. To him, maybe I was just an interesting animal variation in nature. My dad had an animal story for everything. After I didn’t get up for school when Momma called me and I missed the bus, Dad told me I could walk. He said that every year the wildebeests of the Serengeti migrated five hundred miles to Kenya for better grazing. He reckoned I could walk the three miles to school for the sake of my education. I told him that many of those wildebeests were killed by predators on that journey. He said he’d take full responsibility if I were eaten on the way to school.

The one time Momma had mentioned me being queer with Dad and me in the same room, Momma had sworn Dad to secrecy, but I was certain she wrote pages upon pages in her notebook, and I suspected she even added a couple of diagrams that I was too scared to look upon.

“Once God heals Lorraine, nobody need know about her deformity,” she’d said.

Hell, I figured Momma was pissed that God knew about it.

Becky knew. I took some consolation that Becky couldn’t bring herself to use the words queer or homosexual. Becky wouldn’t advertise it. She’d have been afraid to catch it. Besides, Becky didn’t pay attention to anyone but herself and her dumb boyfriend, Kenny.

Since I’d made my kissing mistake with Jolene, Jolene knew. This brought me right back to the question of what Pastor Grind had called about. I needed to go to the barn and tell Dad that Momma had gone to the church, and then I needed to press for information from the nearest all-knowing being: Becky.

CHAPTER THREE

The Wait

When I returned from telling Dad that Momma had gone to the church, Becky was back on the front porch, swinging and gazing at herself in a mirror.

I just looked at Becky and wondered where she came from. “You give the roast permission to cook on its own?”

Becky didn’t answer. She stared into the mirror of her compact and spackled her lips with a layer of Pepto-Bismol–colored lipstick. She licked her fingers and corralled a couple of hairs that had come loose from her French braid, which made me reach up and touch my own mop. That morning I had snared the back with a rubber band and subdued the top with a baseball cap. I pulled off my cap, the rubber band broke, and my hair sprang out from my head. “I bet you wish you had these curls.”

Becky snorted. God forbid she just laugh at something I said anymore. Still, she motioned for me to sit in front of her on the floor of the porch.

I knew what that meant. She wanted to play a game we had played since we were old enough to pull hair and hold a comb. We called it “beauty school dropout.” The object of the game was for Becky to make my unruly hair into some hairdo from her magazines. I didn’t always like the outcome, but I always liked when Becky touched my hair.

We were shaded on the porch, but still sweating. The humidity hadn’t reached the state of locker room closeness yet, but the sun had burned the dew off the grass and warmed the air to eighty degrees. Pants and Sniff plopped on the porch floor beside me when I called them. I rubbed and scratched their bellies—the pleasure loosened their joints and they flailed like they were strumming a guitar. I knew just how they felt. I was slack-jawed and nearly drooling as Becky tamed and braided my hair. That perfect moment was blown to bits when the reason for Becky’s earlier primping barreled up the drive in a rusty Dodge truck. Kenny Hollister.

He was bigger than any of the boys in our class, even though he was a year younger. He wasn’t bad looking if you liked boys, and Becky did. Muscled but lean, he moved like a big cat: agile and fast. He was a natural at any sport he decided to play. It was the deciding that caused a problem. Kenny joined the teams and did well at first, but then he quit—usually after a fight with another player or the coach.

Becky let out a deep sigh. “Be still, my heart.”

I groaned, “Be still, my gag reflex.”

Although she’d braided only half my head, she pushed me to the side, tucked her makeup case behind a pillow on the swing, and hustled to the top step of the porch as Kenny parked his truck near the house.

Becky fiddled with her already perfect hair. “Why’s he got his smelly hunting dogs with him?”

Kenny loped over to Becky. She lingered on the step. Once she could reach him, she kissed him. Kenny wiped lipstick off his face but leaned in for another kiss. She burnished his face and neck with her hands, and then let her arms fall around Kenny’s shoulders and kissed him again.

I had to smile. I didn’t want to kiss Kenny, but I sure as hell wanted to kiss somebody like that.

In the truck cab, Kenny’s dogs, Satan and Buck, barked and snarled. Pants and Sniff jumped at the truck door and barked at them. Kenny had rolled up the windows and left his dogs in the cab, their protests muted, but the truck was heating up. They fogged and smeared the windows with their breath and slobber.

“Lorraine, go get our guest some lemonade.” Becky’s eyes were glued to Kenny. I couldn’t tell if Becky was going to kiss him again or eat him. Becky didn’t take her arms away from Kenny’s neck.

“Morning is more of an orange juice moment,” I said.

“Fine. Get my honey some orange juice, Lorraine.”

“We’re out of orange juice. We just have lemonade, and I’m not going to get it. Sorry, your highness, but it’s my day off.” I fingered my half-baked hairdo and searched for my hat.

Becky harrumphed into the house and mumbled something. Kenny slunk a few steps closer to me and the dogs.

“You could learn a few things from your sister. Actually, you could learn a lot. She knows how to treat a man.” He wiped his mouth again. Both dogs turned their bellies up to Kenny for a rub. Sniff’s tongue lapped at Kenny’s hands and wrists. Kenny baby-talked to the hounds, which sickened me more.

“You can’t hold your licker, can you boy?” he said. “Who’s a good boy?”

It infuriated me that they liked Kenny as much as they did. I credited my dogs with better judgment.

“I could get you a date with one of my cousins. Who knows, you might even enjoy yourself.” He leaned over me. I smelled his Brut cologne. It barely masked the odor of his family’s pig farm.

“I’d rather be autopsied alive.” I shooed the dogs off the porch and stood up, facing Kenny.

“Humph. One of these days some man’s going to slap your smart mouth.” He ran a finger down the side of my jaw. “I just hope I’m there to see it.” He winked.

I swatted his creepy hand away, but he grabbed both my arms above the elbows and squeezed. Just then Becky came out with two glasses of lemonade. Kenny released his hold on me and headed toward his truck.

“Where’re you going, Kenny? I brought you some lemonade.”

“Nope, can’t stay. My chores are done. I’m going hunting. I’m going to run those dogs’ blame feet off. I’ll pick you up later.”

Gravel and dust kicked up from Kenny’s truck and pelted the fiberglass woodchuck diorama Dad had put in the yard the day before. Kenny sped from the yard, barely missing Twitch’s Jeep coming up the drive.

Becky offered his abandoned drink to me. “God Almighty, Kenny’s cute! Did you see the way his jeans fit him? I wish he didn’t have to leave so soon.”

“Hmm, sugar on the rim. Nice touch, sis.” I took the glass from Becky. “You know Kenny, hard for him to hang around here kissing when he could be off killing something.” I rubbed one of the places on my arm where Kenny’s fingernails had cut into my skin. I thought of showing the marks to Becky, but it’d be pointless. Becky was unreachable when it came to seeing anything negative about Kenny. I saved myself the aggravation.

Twitch got out of his Jeep and smiled. “Hello, girls.” He tipped his Twins cap at us, letting wavy brown hair brush against his forehead and cheeks for a moment before he reined it back in with his cap.

I handed him the glass of lemonade.

“Heavens, is it a margarita?”

“Nope, Becky’s lemonade. What’re we doing today?”

Twitch coming was the first good thing I’d seen all day. When he came for me on a Saturday it usually meant he had a job for me—drenching sheep, or pulling a calf, or neutering or spaying somebody’s pet. The pay was just above pitiful, but the labor was my idea of a vocation. Momma would only let me work for him a few times a month and never if it conflicted with a possible shift at the diner. She had forbidden me from taking the full-time summer job Twitch had offered every year since I turned fourteen. No matter how many times I asked, Momma never explained why I was forbidden to work for him.

“I gotta talk with your dad, run an errand, and then I’ll pick you up.” He drained the lemonade and handed the glass to Becky, but looked back at me. “I like what you’ve done with your hair. No makeup or dresses required for this job. Come as you are. You two, hard to believe you’re from the same litter.” He laughed to himself and sidled off to the barn before I could kick him.

“Becky, do you really think Grind was calling about the scholarship?”

“I don’t know. I wouldn’t tell you if I did. It’s more fun to watch you sweat.” She put the drink glasses on the porch railing, stretched her neck out, and balanced her box of Brides magazines on the railing. “It’s probably you in trouble.”

She looked at me, licked her finger, and tore another blushing, blonde, boney bride from the glossy pages. “You’ll never win that scholarship. There’s a morality clause. Do you know what that means, Lorraine? Even if you manage to miraculously beat my GPA, which you won’t, you’re a queer, a homosexual. I haven’t said anything about it before, but you’re a freak and you’ll never win!”

Becky said the words. She spit them like it was nothing, or just some shit in her mouth. She ripped out a picture of a model in a sequined wedding dress and added it to the pile on her white, satin-covered scrapbook.

Dad came around the corner of the house just in time to hear Becky’s last bit of venom: “Like Momma says, the rewards of the faithful will not be squandered on the unholy. Lorraine Tyler, God will burn you in hell for being queer!”

I lowered my shoulder and plowed into Becky. I swept her off the porch onto the lawn, and rolled her down a small hill. A perfume ad pressed against my face. We broke the porch railing, two gnomes, and flattened the hollow chipmunk tableau. Air whooshed out of Becky as I landed on her at the apron of the duck pond. We swatted at each other. She screeched. I yelled from a bruised part of me that I didn’t know I had.

“You take that back!” I might’ve drowned Becky if Dad hadn’t plucked me off her.

“Calm down, Lorraine! And you, Becky, get cleaned up and I’ll deal with you later!” He pointed Becky to the house. Covered in mud, Becky looked like a walking turd. I wished I had Momma’s camera so I could have taken Becky’s picture and submitted it to the senior yearbook committee—with the caption: most likely to be mistaken as fertilizer.

“March!” Dad pointed me to the barn.

I was covered in mud and duck shit. “I hate her! I’m so tired of her being perfect.”

“Nobody’s perfect. I’ve proved that to your momma over and over again.” He pushed at my shoulder. “Calm yourself down. It’s going to be okay.”

I’d never call my dad a hugger, but that day he halfway hugged me. He pulled me into his arms and ducked down so that our eyes met. I knew his look, knew he loved me. I tried to slow my breathing and quell my tears.

He slung his arm around my shoulders again and pushed me toward the barn. “Jesus Christ! You’re a mess.”

“Twitch gone?”

“Yep. Sent him on his way.”

Water spurted and splashed against the side of the cow trough as Dad worked the pump handle. He wet his handkerchief and wiped a clump of mud off my chin.

“Let’s get rid of your mud beard first.” He took another swipe at my face and rinsed the rag before he worked the mud away from my leaky eyes. “You resemble that old raccoon you brought in the house. Jesus, your momma was mad.” He chuckled. “And remember how scared Becky was when the critter jumped on her lap? She don’t go in for animals much.” He laughed so hard he went into a coughing jag.

Dad’s nostalgic inspection of my most recent battles just refueled my anger. I wanted somebody to take something from Becky for a change.

“What’re you going to do to her, Dad? Will you ground her?”

“What happens to your sister isn’t your concern. Your job is to worry about yourself.”

“But, Dad—”

“No buts about it. You’re smarter than this. That’s what gets my goat.”

Then he did something I loved about him, but not always when he did it to me. From his shirt pocket he took out his little notebook and scribbled screwworm 1960 on a page and handed the note to me. Here we went again. Momma recorded sins in her notebook, and Dad wrote out homework assignments in his. I knew the drill. Research the animal at the library and figure out the lesson.

“Most maggots eat dead things.” He paused, lowered his head, and squinted one eye. “The screwworm is a different animal. Learn about it and you’ll know something a

Word Count: 61,700

Page Count: 242

Cover By: Natasha Snow

ISBN: 978-1-62649-550-0

Release Date: 05/06/2017

Price: $3.99