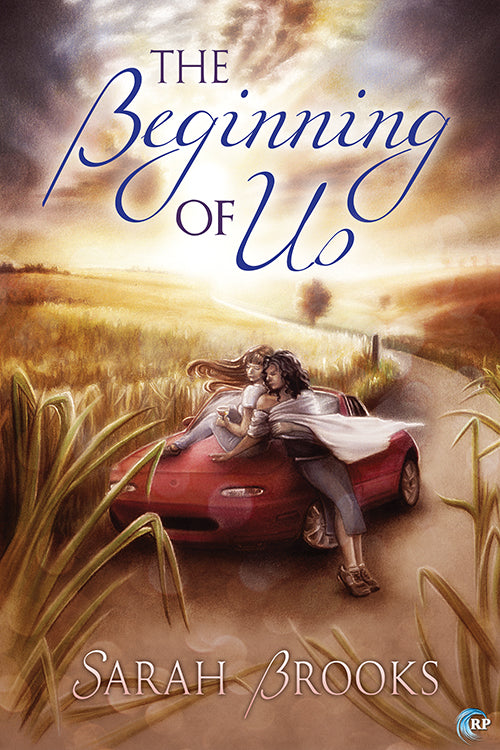

The Beginning of Us

Eliza, where are you? I'm listening, watching, waiting for you. I need you. How dare you run away? Where’s the courage, the fearlessness I fell in love with?

I don’t know what else to do but write. It’s dark in my dorm room, and the wind rattles the panes of my window, and I’m supposed to be driving to my parents’ right now for winter break, but I can’t feel my arms or my legs, and my chest aches because I don’t know where you’ve gone. Or why.

I know I shouldn't have fallen in love with my professor. But you inspired me when you stood in front of the class, telling us to find our authentic selves. And I did—with you. How could I know that you would be so afraid of this, of us? That you'd be so terrified of . . . yourself? Wherever you are, Eliza, hear me—and come back to me.

Love (yes, I'll write that word, Professor), Your Tara

Reader discretion advised. This title contains the following sensitive themes:

drug useCaution: The following details may be considered spoilerish. Click on a label to reveal its content.

Length: Novella (15k to 45K words)

Heat Wave: 2 - Kisses and touches without love scenes

Erotic Frequency: 2 - Not many

Genre: contemporary, new adult, romance

Tone: intense, literary, realistic

Themes: angst, college life, coming of age, coming out, commitment, epistolary, first love, self-discovery / self-reflection

The Day You Left

WHERE ARE YOU?

Eliza!

WHERE. ARE. YOU?

I’m listening for you, but all I hear is the wind outside the window, and so I hate the wind because I want your voice. Need your voice. I need you.

How dare you leave me?

I can’t be in this world without you. That’s the truth that presses me to the floor. The world without you in it doesn’t matter.

I don’t care how that sounds.

Where have you gone?

I’ve checked my email every ten minutes since this morning when you failed to show up to give the final exam. Nothing from you. And nothing from you. And still nothing from you. You, who used to send me so many messages and poems and links to online art installations and photographs you thought I should write about, you have become mute. You have disappeared.

I composed a long email to you, all about how much I need you in my life and how I’ll understand and forgive any explanation about why you’re not here, if only you’d write me and tell me where you are, but then I deleted the email.

Then I wrote this one: FUCK YOU! WHERE ARE YOU??? But I didn’t send that one, either.

All afternoon, all night tonight, I checked my email every few minutes, sure you’d send me a note that would explain everything. You wouldn’t just leave me, would you? You’re scared, but you’re not a coward. And you love me. You wouldn’t leave without an explanation.

Would you?

Every time I refreshed my email, I’d be sure you’d have written. My heart would beat faster, and I’d close my eyes, and then—nothing.

No missed calls on my phone. No text messages. I even walked down to the Union to see if you’d slipped a note into my mailbox. Nothing.

Eliza. Only this silence hurts more than your sudden absence.

At ten or so tonight, I allowed myself one final email check, closed the web browser, and then stared out my window for a long time.

I just want to talk to you.

So I’ve opened up this Word document, to talk to you here. I won’t allow myself to look at email again. If you haven’t written me today, when you must know I’m reeling from your absence, you won’t write me.

This can’t be happening.

I need to breathe.

I can’t breathe.

Breathe, Tara, breathe.

I don’t know what else to do but write. It’s dark in my room and the wind rattles the panes and outside it’s dark and I’m supposed to be driving south to my parents’ right now for winter break . . . but I can’t feel my arms or my legs . . . and my chest aches because I don’t know where you’ve gone. Or why.

Eliza!

If I type these words to you, they might be words you’ll never read, but then again, maybe while I’m typing I’ll look up to see the door opening, and you’ll be there, and you’ll laugh and say I should’ve had more faith.

So I’ll keep typing.

Tara, breathe.

Everything I thought I knew about you is dissolving. What if these past months weren’t real? What if you were never real?

But you were. You are. Right?

You are. Wherever you are, Eliza, hear my words—and come back to me.

The Day After You Left

It’s so cold this morning, I can see my breath. My first impulse when I woke was to check my email. I thought, surely she’s written by now. But in all the junk emails, the electronic Christmas letters from my friends, the reminders from Grace College to have a safe break, nothing from you. WHY?

Why would you keep this cruel silence?

All I can do is write to you here, in this document. Maybe my typed words will reach you, somehow.

First, I need to tell you I loved you immediately.

Even before I walked into your senior seminar class, I loved you for the course’s ostentatious title: Against the American Canon.

But then I met you.

You were standing at one of the whiteboards, scribbling notes in black marker across the entire surface, the other three walls already full of your writing. I’d arrived early for some reason, and you gazed at me for a long moment when I entered, your dark eyebrows raised above your intense brown eyes.

“You’re early.”

“Yes—sorry.” I couldn’t tell if you were impressed or irritated, but I stuck out my hand and you shook it, and your hand was so small and delicate, a surprising hand for someone who seemed to fill the room. I noted your long, dark, wildly curly hair, and that you were wearing black.

“I’m Eliza Moore. And you are . . .?”

“Tara. Tara Haus.”

“Well?” you asked me, waving your arm in one sweeping motion at the boards. “What do you think?”

“I—” And suddenly, I forgot everything I had learned at Grace College in the three years before that moment and everything I’d learned in high school. Speech left me entirely. I sensed my open mouth, the way my eyes widen when I panic.

“When you’re ready—tell me,” you said, grinning, gesturing for me to have a seat at a desk. I did, and you kept scribbling on the whiteboards, and soon other students began to straggle in, and you greeted each one with the same intensity and the same question, so I knew I wasn’t important to you, hadn’t made an impression. I’d never been that kind of student. Professors had never invited me to their houses for dinner or out to a bar for conversation. I’d always been the obedient student, the stereotypical good Iowan farm girl. Or at least that’s how I used to characterize myself. Before you.

That first day I met you, the moment the digital clock on the wall reported the start of class, you pulled the door shut and began class. A student tried to come in late—we could all see him through the long rectangular window of the door—but you didn’t acknowledge him. No one came late after that first day.

“What is America? Who are the authors of America? Who gets to decide who we remember and who we read? Why does any of this matter?” You threw questions into the air, and we struggled to catch them, or at least examine them before they popped like bubbles. I was writing down everything you said, laboring to keep up with you, when a hand—a small hand—closed my notebook. “You don’t have to write it all down,” you said. “I’m just trying to get you to think.” Everyone laughed a little, but it was nervous laughter. I wasn’t the only one intimidated by you at first.

You threw posters and cardboard-backed prints of famous American art onto the floor in the middle of the circle of desks, and you told us to get up, walk around, be prepared to share our observations. Again, my mind blanked. I had never wanted to impress a teacher as much as I wanted to impress you, and that was strange in itself, but what was even worse was that I had no thoughts in my head. I walked around the room in a stupor, seeing nothing. God, writing this makes me wonder why you ever noticed me at all. All the words we’ve spoken to each other since then, and that first day in your class, I couldn’t conjure up a single thought.

Luckily, that jock in the red T-shirt dominated the conversation when we gathered in a circle again. Where the hell was the US flag, he wanted to know, because the only good art has soldiers and the US flag. We all shifted in our desks, wondering how you would handle the guy, and how he had convinced the registrar he met the prerequisites for a senior seminar in the English department. You smiled indulgently at him and then proceeded to point out American symbols in the paintings at our feet.

The guy shrugged. “Fine. But where’s the fucking flag?” We all knew he was just trying to provoke you, but it was embarrassing. I could tell you were new to Grace—just from your black high heels and your black jacket and fashionable skirt—and I didn’t want you to get this impression of our college.

“America,” you said, leaning toward the guy with your hands gripping his desktop, “is more complicated than you want to make it,” and it was such a comical image, this small professor with her wild black hair and her city clothes basically threatening a hulking football player who had probably only signed up for the class because he thought it would be easy, that many of us began to snicker. The guy shot us glances, and then erupted. He stood and shouted, “Fuck you all!” and stomped out. A few people cheered.

I couldn’t stop looking at you. You watched him go, your dark eyes flashing, and then the moment the door closed, you took a deep breath and said, “Now we can learn something,” and we all laughed, and then you seemed to take us all by the hands to lead us into the depths of America: questions, images, more questions, discussion. By the end of that first class, my mind was swirling. I loved it.

I did fall in love with you that first moment, but in a pure way. So many of my professors at Grace had been dry and predictable, all of us in straight rows, taking notes while the professor lectured about Dickens or Shakespeare. But you were different. You energized the classroom and made our learning feel relevant. I had become an English major because in the middle of my freshman year, when I was a chemistry and math double-major, I realized I would never be the person I thought I should become if I stayed limited by differential equations and controlled variables. You reminded me all over again of the way the words of literature stir something in my soul.

Yes, I fell in love with you immediately. I was a senior, and it was as if I’d been waiting for your class all of my college years. I fell in love with your mind first.

How you would grin at that.

What I’ve never told you is what happened in the weeks between that first class and the first . . . moment between us. Something changed in me even that first day. I was supposed to meet Jacob, the guy I’d been dating for a year (remember? I told you about him when we drove to Madison) for lunch that day. As I walked across the Commons, I could see Jacob standing at the big picture window in the Union that looks down onto the track and the river bluffs, and I recognized—with a pang—that the day before, that silhouette would’ve triggered greater affection in me. It was as if something had just turned off inside me. As I approached him, I told myself he looked the same: broad shouldered, tall, sandy haired, his profile revealing Norwegian-American heritage in his square jaw, his long, narrow nose. He wore nice jeans and a green fleece, and he stood with his hands clasped behind his back. Already, he looked like the doctor he planned to become: capable, superior, prepared. But as I stood in the middle of the Union Commons, I knew I didn’t love him. How is it possible that two hours of your American Canon seminar did that to me? I didn’t connect the two at the time, but I do now. You bewitched me, Eliza.

Just then, Jacob turned toward me, and I had the impulse to run away and hide. But where would I have hidden from him on Grace’s small campus? I wondered, in that moment, what kind of person I was to want to flee from the loyal, good man I had dated for a year.

But I didn’t run; I waved at him. I know you only know Jacob from the little I’ve told you, but he’s a good man. The problem is that his goodness comes with blindness. He’s a man of such tradition that he can’t imagine alternatives. And he’s not observant of small details. Maybe, when he’s a doctor, he’ll learn to pay more attention to the signs and symptoms that indicate larger medical problems, but he’ll never notice the subtle shifts in human emotion. He didn’t notice that day that anything had changed between us. Instead, he strode across the Commons and pulled me into his arms, kissed me fully on the lips, and told me, as he always did, that he hated time away from me.

You asked me once if I thought Jacob was overly dependent on me. It’s true that he loved to be with me more than anything else, which is unusual in a man. He would choose a quiet dinner with me over a night out with the guys. But he has his dignity, Jacob. He did let go of me when I asked him to—later.

That day, the first day of your seminar, Jacob and I sat in the Grace Café at a table by the window. It was August, and the day was sunny and bright. On the river bluffs, the oak and hickory trees were still green, but soon they would turn brilliant yellow and orange and red. I stared out the window, thinking of fall, thinking maybe that was all that was wrong with me: the change in season, the melancholy of the first day of a new semester.

And then my mind wandered to you. I suppose Jacob was still getting our food, I don’t know. What I know is that instead of thinking about my thoughtful boyfriend, I was thinking of the sheen of your curly black hair and the incredible delicacy of your hands.

“So, how’s your first day of class going?” Jacob asked, appearing suddenly, startling me. He set two trays in front of us; he hadn’t asked me what I wanted for lunch, but he knew what I liked.

“I think I’m going to transfer out of my senior seminar.” I didn’t even know I would say this until the words tumbled from my mouth. I never told you this part because I knew you would take it as a personal affront to your teaching.

“Really? How come?” In his two large hands, he held an enormous burger stacked with two patties and bacon and cheese. He took a huge bite. Usually, I laughed at his appetite, but his chewing and eating and the grease of the burger only disgusted me that day.

“It’s just not going to work for me.” I couldn’t articulate it any more to myself. I didn’t understand. Something twisted in my chest; my legs and arms became strangely numb. I closed my eyes and tried to blank you out of my mind, but then there was your voice, the flash of your grin—

“Tara?”

He startled me out of my thoughts, and my eyes flew open. Jacob was still holding his burger, now half-eaten, but he was staring at me, his hazel eyes wide.

“Are you okay?”

“I think I’m going to go drop that class right now.” And I left him with our two trays of food, which I knew he would finish by himself. I called over my shoulder to him, “I’ll see you tonight.” On weekdays, we always met in the library to study. People said we were inseparable.

Of course, I didn’t drop your class, as you know. I didn’t even go to the registrar’s office. Instead, I walked furiously (why was I so angry?) down the hill from Grace to the bike path that curved along the Green River. My shoulder bag bounced against my back, I was walking so fast. And, inexplicably, when I reached the secluded grove of birches on the river’s edge, I threw my backpack down, collapsed onto the bench there, and burst into tears.

No, I never told you this, either. I thought you would think I was crazy, to be so emotional about you the first day I met you. But it wasn’t just you. I’ve told you about how difficult that summer had been for my family since we’d decided in June to sell our farm and my parents had moved into Davenport, abandoning the open expanse of land on which my younger sister and I had grown up. At the time, I explained my tears to myself that way: I was finally releasing all the stress of that summer, now that I was back at Grace and away from my father’s sullenness and my mother’s wringing anxiety and my sister’s sadness. But I sobbed and sobbed, rocking myself on that bench by the river. I sobbed until my stomach muscles hurt.

Then—I don’t quite know how to explain this—the sun burst through the tree branches in this star of light, and a sense of calm washed through me. I may no longer believe in God, but my childhood faith is still with me: I thought of that sun star as God, or at least as Something More. Comfort washed over me. I thought of you again: your energy in that classroom, the way you raked back your curls with an impatient hand so you could more clearly see a student talking. I had never thought so much about a professor before, but I decided, there in the sunlight beneath the birch trees, that it was just because you were a different kind of teacher.

It’s an understatement to say you’re a different kind of teacher. You were—are?—a rare kind of teacher. After just two weeks of the semester, it seemed the entire campus was talking about you. You, Professor Eliza Moore, the new hire in the English department. It wasn’t all complimentary. Some people, like my friend Trace Waller, who was in your Humanities class, basically hated you. Trace always complained that Humanities was a basic requirement at Grace, even for students pursuing a physical education degree. I’d guess that usually the history and English professors who teach it accept their students need a slower pace. Not you. You taught Humanities with the same intensity you taught our American Canon senior seminar, which was filled with English majors. Trace hated that you wanted them to think and that you expected them to write so much. But you couldn’t have been otherwise. It’s who you are.

I don’t know why I’m writing this in second person, as if you’ll read this someday. As if suddenly everything will be okay, and you’ll rap loudly on my door, and I’ll open it and run into your arms, and we’ll drive away together into the sunset. What did you say again and again in American Canon? The story of American literature is the dream deferred: the dream people pursue and then watch explode. We’re another one of those stories, aren’t we? And I’m writing it alone here, and the ending is that our dream exploded like all the others. I can only talk to you in my writing, now.

It’s dark tonight. I’m sitting in the corner on the floor with only the light from my laptop screen, and no moonlight is streaming through the window. It’s eerily quiet. I don’t think anyone knows I’m here. Does Grace allow students to stay here over winter break? It seems the rules might be different for Amundson Village, since it’s all seniors. But it’s so quiet I’m sure everyone is gone. Everyone except me.

I have to keep writing. Every time I stop to wonder where you are, I feel myself spiraling down into sadness again. I have to keep telling our story. Maybe I can write us a different ending. But that may be up to you.

Word Count: 31,100

Page Count: 120

Cover By: Simoné

ISBN: 978-1-62649-105-2

Release Date: 01/25/2014

Price: $2.99